The Men Who Made America’s Self-Made Man

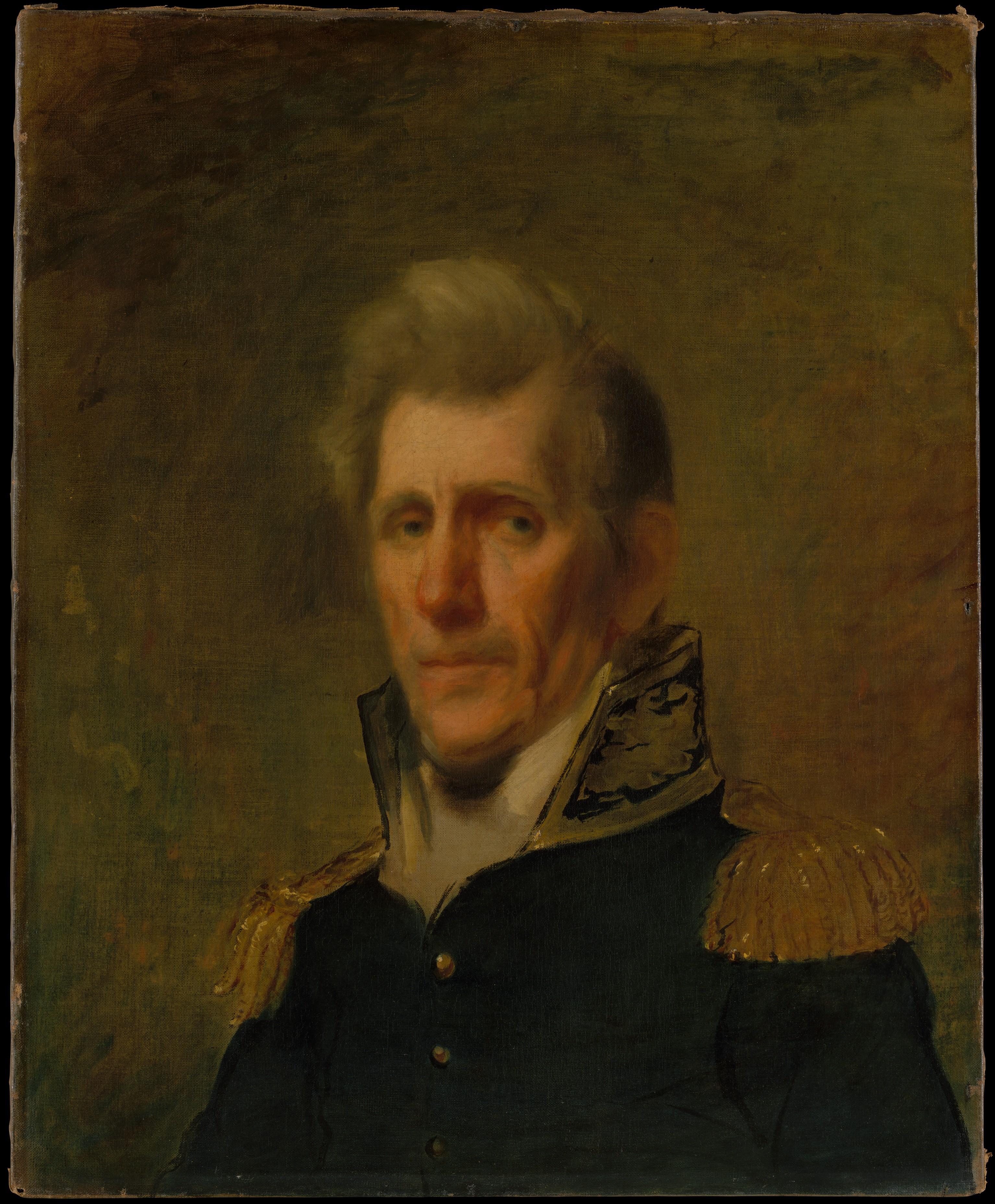

Andrew Jackson, by Thomas Sully, 1824. [National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution]

Back in the days when only aristocrats and spiritual leaders could hold political and cultural authority, there was no pride in claiming to be self-made. Instead, an assertion of self-made success was dangerous, both blasphemous and foolhardy; it put souls and social relationships at risk. It took two revolutions and their ambitious storytellers to reverse those values. The first, the American Revolution, flipped elite origins from a source of power and esteem to targets of anti-aristocratic invective. The second, the 19th century’s industrial and financial transformations, replaced appreciation for self-improvement to serve with paeans to wealth.

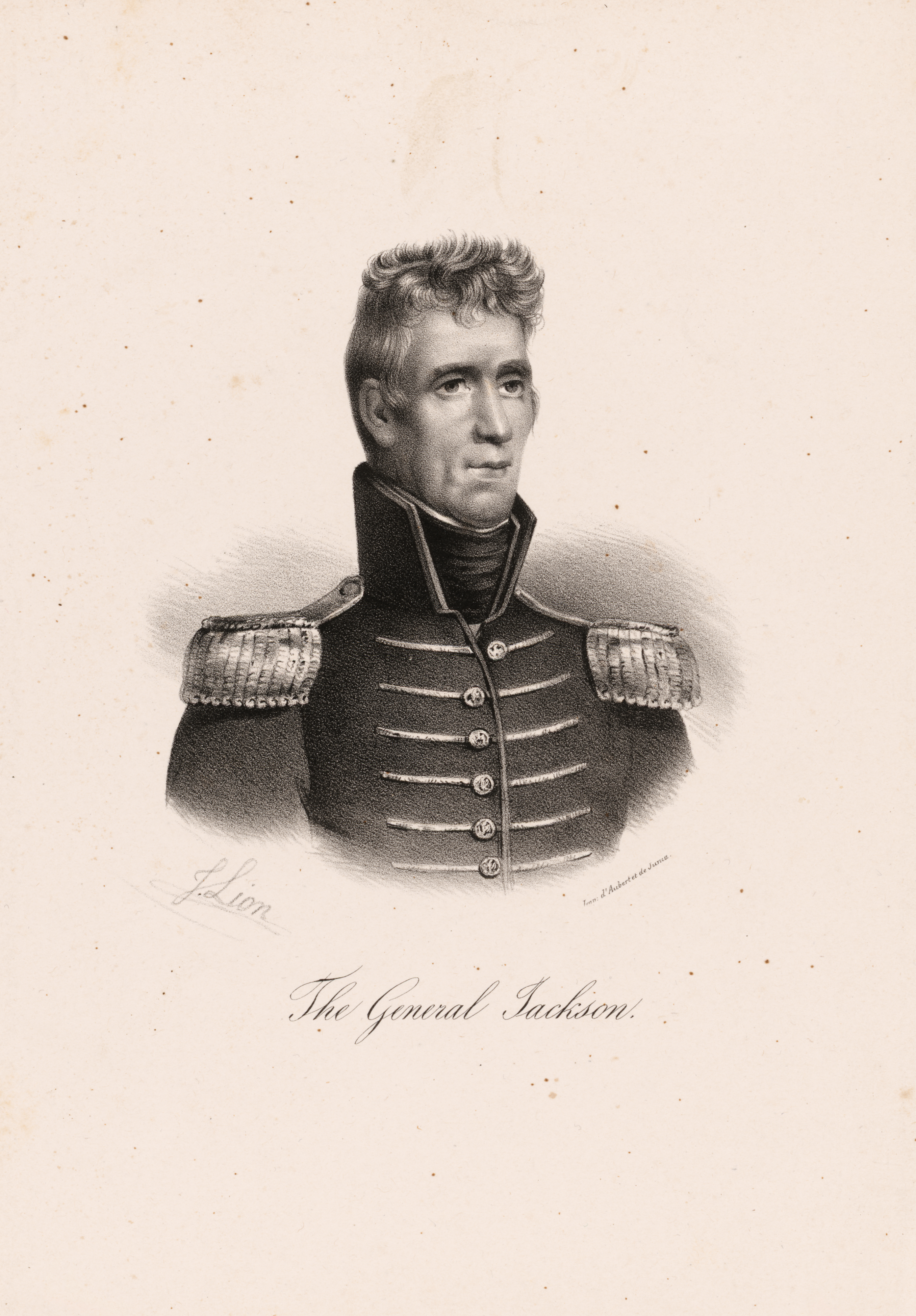

No one’s image exemplified the post-Revolutionary anti-aristocratic ethos more intensely and intentionally than that crafted by Andrew Jackson, the first president from the western territories and the only general to be elected president since George Washington. Supported by the votes of men enfranchised since the Revolution, Jackson was fiercely loyal, demanded loyalty from others, and exacted retribution without hesitation. He seemed to have two personas, one forceful, raging, and deadly; the other affectionate, polished, and charming. His dual identities encompassed military leadership and being a skilled lawyer and land speculator who often quoted the Bible.

Jackson was born in 1767 and raised by his widowed mother until her death when he was fourteen. He lost his brothers during the Revolutionary War and received a head wound as a boy from a British officer in punishment for defiance. This background enabled Jackson and his supporters to credibly construct his childhood as harsh. In reality, however, his mother’s family was prosperous, and he grew up in an affluent uncle’s home. He attended a private academy and taught for a while, receiving enough schooling plus legal training under the guidance of influential lawyers to practice law by 1787. At fifteen he even inherited about £400, approximately $85,400 in 2024, which he quickly squandered. Invaluable connections among the small group of professionals in the territory that became Tennessee made for highly profitable land dealings, including in regions of questionable legal status, plus a successful entry into politics in his early twenties. Despite so many advantages — unusual in western regions — he and his advocates later highlighted the tragic elements and ignored the blessings. They narrated Jackson as a self-made and self-fashioned frontier hero, which attests to the growing force of that mythology and the corresponding weakening of narratives about community support.

Jackson built his reputation for resolute discipline and relentless patriotism by leading volunteer troops effectively against indigenous peoples and veteran British forces in the Southeast, culminating in January 1815 with a remarkable victory in New Orleans that brought him fame and made him an attractive candidate for national office. An assortment of storytellers then took up the challenge of making this war hero into a president, and the mythmaking began. “ANDREW JACKSON was born a great man — he was born free,” concluded an 1818 biography that rapidly went through multiple editions. Not only did Jackson benefit from his free birth, according to S. Putnam Waldo, but as a westerner he could ascend unencumbered by “a monied or a landed aristocracy” like that which dominated the nation’s “settled” regions. There, “an insulated being … without the influence of friends to aid him, or without funds to procure them, can hardly hope, with the most gigantic powers, to place himself in eligible circumstances.” In “the new states,” however, Waldo asserted that “each individual may almost be said to make a province by himself.” There, Jackson could “rely solely upon intrinsic worth and decision of character, to enable him to rise rapidly with a rapidly rising people.” Waldo depicted a drama of “arduous toils, the severe privations and the excessive fatigues, by which he acquired his fame.”

Despite Jackson’s good fortune through mentors, inheritance, and professional partners and connections, Waldo asserted that Jackson entered adulthood “entirely alone” and without “extrinsic advantages to raise him into life.” Continuing with that theme, “he sought no aid out of himself, and he received no aid but what he commanded by his own energy.” Neither Waldo nor anyone else mentioned Jackson’s squandered inheritance or numerous advantages. Waldo’s narrative contained all the elements of self-making praise, plus plenty of drama and links to “a rapidly rising people,” but still did not use the phrase itself. Jacksonian-era political combatants would soon thereafter utilize the phrase as they competed for the cultural authority that could support political authority.

Pacesetting those competitions, Jackson’s allies devised a concerted storytelling campaign to make a president out of the “Hero of New Orleans.” Aiming for 1824, they built a network of supporters based in Nashville, Tennessee, but connected throughout the country to local political committees and newspapers. Sometimes, where favorable newspapers did not exist, they established them; their stories had to get into the wind. They raised partisanship to new heights, and in the hotly contested four-way presidential race of 1824, Jackson achieved a plurality in both the popular and electoral counts, only to lose the race in the House of Representatives. Allegations that a “corrupt bargain” had cost him the victory became a powerful rallying cry for the next four years, marshaled as evidence of the need for a hero who could reform national politics. The innovative and brilliant workings of that long campaign constructed and broadly disseminated the image of a self-made hero who could revive the true, pure spirit of America’s revolutionary generation, and who, like George Washington, was willing to sacrifice his peaceful rural retirement to serve the nation. Much of Jackson’s persona was refashioned for this campaign, including the fiction that he was a reluctant candidate. The outcome was a landslide victory in 1828. Stories — this story — mattered, not realities, and the election rewarded the mythmakers.

Along the way to 1828, candidates’ supporters began to tell stories in a language that had seen little use outside of moral judgment — condemning drunkenness or praising godliness —but was available to judge worthiness for the national stage. William Crawford of Georgia, one of the four leading presidential candidates in 1824, received the newly honorific term “self-made” in a lengthy 1824 essay Thomas H. Hall addressed to “The Freemen” of the North Carolina district he represented in Congress. Signaling that the phrase “self-made” was still germinal and unusual, he self-consciously attempted to define and elaborate it: “Crawford is what we call a self-made man; has risen from obscurity by his own exertions.” Hall contrasted Jackson with Crawford, who was a man of “integrity and ability” and whose “manners and deportment were always those of a polite gentleman.” According to Hall’s diatribe, Crawford could be self-made as self-improved even if not self-taught in Jackson’s rough manner. A space-filler “Maxim” highlighted at the end of this campaign piece declared simply: “Merit should be the only passport to office.” In that same North Carolina newspaper, an unsigned essay illustrated how the phrase could still be used to denounce rather than praise. Although the “nation owes him a large debt of gratitude,” a long list of Jackson’s actions exposed him as either “ignorant or despotic,” with “uncultivated notions of military tactics” and a mere “smattering knowledge of law.” From some perspectives, of course, those very attributes were beginning to sanctify Jackson as self-made in what was becoming its positive sense — but not in this partisan enemy’s camp. What is significant here is that the status of “self-made man” was still conditional, tentative, and subject to partisan debate: it was possible either to praise or deride with the concept. Self-making did not yet assure an indisputably heroic or positive narrative.

The next year, as the campaign accelerated toward 1828, an essay on Jackson’s behalf appeared in many venues, loaded with melodramatic descriptions of origins and triumphs that forcefully advanced the self-made myth, both as regards Jackson, and generically. It began, “If the present age can boast an ornament for whom history furnishes no example … that man is Andrew Jackson.” Because he had been “deprived in his boyhood” of his family, “he stood alone, and unassisted” like a “solitary oak that stands forlorn.” With “neither the pride of ancestry, nor the patronage of office – he was not the fondling of a dominant aristocracy, but had to struggle for subsistence in the darkest hours of adversity, and to encounter vicissitude after vicissitude” with only the forces of his “energy and self-possession.” Intriguing reflections mixed causal factors between the “Nature [that] designed him for a great man” and the “force of circumstances.” Neither influence alone could form a hero of such magnitude: “poverty, and self-reliance” had to combine with “natural qualities.” Thus, although “the ancients would have attributed the successes of Napoleon Bonaparte to the decrees of destiny,” in an era with “kings and sceptres alike sinking into unimportance, and non-entity,” it would be inappropriate to attribute Jackson’s rapid march “to honors, and popularity” simply to “fortune … [a] capricious deity.” Instead, “Talents, and not the auspices of supernatural protection” provided the foundation for both Napoleon’s and Jackson’s achievements. Fortunately, however, unlike “the conqueror of Europe,” Jackson was “the friend of man, the soldier of liberty” who would not “prostitute his principles at the unhallowed shrine of ambition.” Unlike the anti-aristocratic praise typical of the time for men who educated and improved themselves to serve, this hyperbole relieved its conquering hero of debts to any community. Instead, self-making appeared here, as it would increasingly in stories to come, to be the lonely success of a solitary oak that eclipsed the forest. Just as strikingly, this encomium to Jackson also denied that he had benefited from “supernatural protection,” which would have been heretical not too long before.

Two years after the fateful 1824 election, the heat of anti-aristocratic polemics on Jackson’s behalf continued to rise. A Jacksonian from Kentucky, Joseph Le Compte, told his congressional colleagues that Westerners worried that the practice of selecting presidents from previous Cabinet appointments as in 1824 was “likely to grow into a dangerous precedent.” The “hero of New Orleans” deserved esteem because he “was self-made; he rose by merit alone.” Not only had he “made” himself, but by saving “the great commercial city of New Orleans,” Jackson had “saved the Union.” Beyond the puffery, Le Compte contrasted his candidate, who “owes nothing to patronage,” to the elites who owed everything to it. That anti-aristocratic contrast animated the core of self-making’s force and appeal as it migrated outward from the moral spheres of preachers, educators, and public servants and into spheres of political power.

This budding political genre of stories about self-making rarely aimed to set godly examples for youth, whether positive or negative, and focused instead on polemics about ambitious men. By the 1820s, the self-made man concept had begun to acquire enough cultural authority to make it an attractive rhetorical tool to enhance men’s portrayals and their claims on public resources, including esteem and votes. A story of self-making, however disconnected from fact, was becoming a form of political certification. It also highlighted contrasts between people who mattered in the public sphere and those who did not. Of course, White males alone had the potential for self-making in these myths and fables. Necessarily, everyone else and their contributions were rendered invisible. In stories of self-making that foregrounded the solitary oaks, the forests constituted by almost everyone else — women, people of color, the working classes, the poor, and even the putative “oak’s” own family and connections — were invisible, except as figures protected or subdued by the hero himself.

As a surprising reminder that nothing is fixed, intuitive, or self-evident about the ideology of self-making in America, in this early stage of its evolution people who were merely rich but did not engage in political competitions were also invisible as subjects of the myth. For example, John Jacob Astor built astounding wealth during these decades but had no religious or patriotic credentials and, therefore, did not qualify as self-made despite his relatively obscure origins. His time for those accolades would come in a few decades. Elites competing for political authority, on the other hand, were visible but ineligible for praise as self-made if their opponents identified them as aristocrats. In this new genre of folklore, elites’ self-improvement to serve, following the Founders’ models, did not guarantee prestige. A candidate’s initial advantages created toxic political disadvantages and had to be hidden. Thus, elites initially served anti-elitist mythmakers only as foils — until, that is, they figured out the game and turned it against their rivals in the coming decades.

But who were these “aristocrats” who, by contrast, ennobled the self-made? The category could include any number of figures, not just beneficiaries of inherited wealth or social benefits, but also formally educated people; businessmen who sought government subsidies for transportation projects, such as roads and canals, that would help them profit from their own investments; boosters who sought federal aid for projects that would advance their regions and the nation; or political appointees. Anyone might qualify as aristocratic, essentially, who stood as an obstacle to someone else’s ambitions. “Aristocrat” was becoming a catch-all political pejorative, contrasted against “self-made” as a catch-all political encomium. By the 1830s, one’s allies were best defended and promoted as self-made men, poaching the respected meanings of this phrase from the realms of preachers and public servants to justify ambitions and claims on public resources.

The profusion of broadly trumpeted political rhetoric in stories of self-made success made the concept available and attractive for other storytellers, including those wanting to praise preachers and other public figures for their self-improvement and service. For example, in 1843 a newspaper praised a then-esteemed but now-obscure preacher as “a self-made man in every sense.” In contrast, directly below that article, a single sentence announced, “The death of John Jacob Astor, for several years past regarded as the wealthiest man in the United States.” Merely getting rich did not yet qualify Astor as “self-made.” It took another revolution to spread that notion into the realm of riches, where successful businessmen like Astor resided.

Across the second half of the 19th century, industrial and financial upheavals shaped that second revolution, which generated both astounding material abundance and harsh inequality. A cultural and political landscape arose in which the label “self-made” was available to wealthy titans as they sought esteem and power. That movement didn’t come without resistance, however, tied as it was to the century’s heated contests to define American ideals in tumultuous times. For example, after the Civil War, Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, compiled biographies of “self-made men,” none of them wealthy, but all of them dedicated citizens, such as Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. Despite her fame, her book sold poorly, whereas James McCabe’s The Great Fortunes was wildly successful with its biographies of rich men, including Astor. The rise of vast new fortunes and new media to tout them created a cultural landscape in which the myth of self-made success became a rhetorical tool for tycoons like Thomas Mellon, Andrew Carnegie, and Henry Clay Frick as they and their supporters claimed cultural authority.

Since the late 19th century, the myth of self-made success has become so tightly linked to financial success that individual wealth seems like the term’s natural meaning. Nonetheless, the history of storytelling about self-making provides an antidote to that now taken-for-granted myth, reminding us of its origins in praise for public servants — and people who claimed to serve the public — not tycoons.

Excerpted from Self-Made: The Stories that Forged an American Myth by Pamela Walker Laird. Copyright © 2025 Pamela Walker Laird. Excerpted with permission of Cambridge University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.