Complicit in the Business of Indoctrination and Incarceration

Girl Scout troops of all ages at the Minidoka Relocation Center in Jerome, Idaho, where over 13,000 people of Japanese descent were incarcerated from 1942 to 1945. [National Archives]

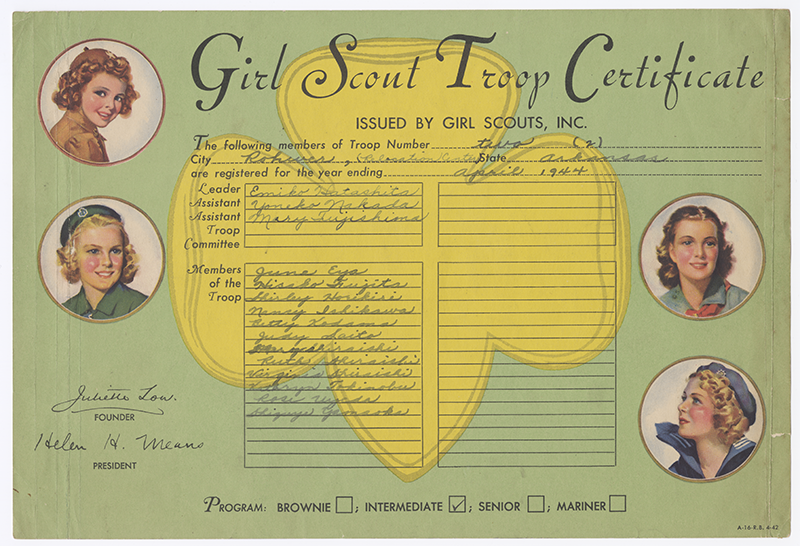

In spring 1944, the twelve members and three leaders of Intermediate Troop 2 at Rohwer Evacuation Center in southeastern Arkansas — one of the ten centers incarcerating Japanese Americans during World War II — inscribed their names on an official form from the Girl Scouts of the USA. A large yellow trefoil takes up the center of this green “Girl Scout Troop Certificate,” one of the featured items at the Japanese American National Museum’s exhibit on coming of age in the World War II incarceration centers. Circling the trefoil are the images of four white girls: a curly-headed brunette (looking very much like Shirley Temple) as the Brownie; a blond Intermediate; a Senior with the distinctive scarf; and a Mariner, blond and curly-haired liked the Intermediate but wearing the seafaring blue and looking up as if she’s reading the sky for navigational signs. All are smiling; all have rosy cheeks. They are the picture of the ideal Girl Scout: cute, competent, healthy, enthusiastic, innocent — and white. Two preprinted signatures stand out in the lower left: a facsimile of Girl Scouts founder Juliette Gordon Low’s and that of Girl Scout president Helen Means. Along the center trefoil are preprinted lines for troops to write in their information: city, state, year of membership, leader, assistant leader, members. This is the same document that troops across the country would have used. But in the section for city and state on this particular certificate, the information stands out: Rohwer, Arkansas. And as if the writer experienced an afterthought, or a sense that no one outside the community would even know where they were, someone had penned in “Relocation Center” in parentheses after “Rohwer.”

This green sheet — probably a ubiquitous part of Girl Scout life in the 1940s — is full of contrasts. We see the “wholesome” vision the Girl Scouts had idealized since the 1910s, a vision of “free,” “intrepid,” and “innocent” white girls, and the reality of the imprisonment young Japanese American girls and their leaders were experiencing. It leads us to consider the complicity of the Girl Scouts of the USA (GSUSA) in the imprisonment of Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans, or Nikkei, during World War II, and it forces us to ask how the US government used the concepts of Girl Scout “courage” and “innocence” to hide the horrors of its imprisonment and treatment of Japanese Americans and Japanese in these incarceration centers. That list of names does something else, too: it pushes us to ponder what Japanese American girls and their parents made of their membership in this national organization that brought its badges, parades, troops, and pictures of cheery white girls into the incarceration centers.

In February 1942 President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized the US Western Defense Command’s order to remove and incarcerate over 100,000 people of Japanese descent. Girl Scouts immediately became involved in this effort. Soon after the removal was ordered, the Seattle Girl Scout Council requested monies from the Girl Scout International Fund to help with what was euphemistically known as “evacuation” of girls in their area, one of the largest regions of forced relocation. At first the Girl Scout National Board voted to table the vote on Seattle’s request until they could gather more information from the American Red Cross, the Foreign Policy Association, and a scholar from Western Reserve University, Grace Coyle, who was, as the board put in its minutes, “making a study of the Japanese evacuation centers for the government.” Eventually, however, Constance Rittenhouse, the president of the national board, signed an agreement with the War Relocation Authority (WRA) to provide Girl Scouting in all the camps. Because the US government wanted to encourage “evacuee identification with groups typically American in concept,” it would help carry out a full Girl Scout program for girls ages seven to eighteen. In signing this official agreement with the WRA, the Girl Scouts was complicit in the business of indoctrination and incarceration.

Yet even before the national board made any decision, local councils were getting involved. At the Fresno Assembly Center, a temporary detention center in operation from May through October 1942, where Nikkei were taken before being sent to the permanent, more inland incarceration centers, the executive secretary of the Fresno Girl Scout Council gave lectures on leadership to the leaders of the newly formed troops in the assembly center. By September of that year, the national board had approved the decision to organize girls in incarceration centers as “lone troops,” meaning they weren’t affiliated with local councils and regions. The troops would be run under the direction of each center’s community service director, a WRA position, who would appoint troop leaders from among their own employees and from those imprisoned. The community service director would also serve as a permanent member of the troop’s advisory council. Girl Scout field directors, the same paid professionals that had made forays into the American Indian reservations and boarding schools, regularly visited the incarceration centers, giving talks on Girl Scouting and “leadership,” that ubiquitous yet somewhat unclear trait that Girl Scouting promotes throughout its history. Interestingly, by February 1943, the national board carried a motion that “national and local publicity on Girl Scout activities in Japanese relocation centers be permitted, emphasizing, however, that Girl Scouting had been undertaken in these centers at the request of the federal government.” In other words, all publicity was to obfuscate the Girl Scouts’ own agency in participating in the centers, deflecting responsibility to the government.

It’s not at all clear from these brief archival records what prompted the decision to avert responsibility. Was there concern about participating in the imprisonment of innocent people? Certainly by 1943 there was a national outcry about this injustice, even if it wasn’t mainstream, and one of the major sister organizations that the Girl Scouts recognized, the YWCA, had explicitly stated that the removal of Nikkei was about “race” and “war hysteria.” Was there concern that the quality of the programming would not be up to national standards, a frequent rationale used to legitimate discriminatory practices and segregated troops? Was there worry that Girl Scouting would somehow be tainted as an activity for unworthy “needy” girls, even enemies of the state? Would participation in the removal efforts somehow distract from Girl Scouts’ efforts to expand, as the national board of directors had approved the program “A Million or More by ’44” in 1942? While we don’t know the answers to these questions, we do know that the Girl Scouts agreed to participate in the incarceration centers, and unlike the YWCA, it came with no voiced disinclination to join in a racist endeavor. According to GSUSA records, by 1943, all the incarceration centers had Girl Scout troops. Giving the girl prisoners a taste of a group “typically American in concept,” the Girl Scouts played a key role in indoctrination at the incarceration camps, indoctrination that was in line with American foreign policy, with dominant ideals of white girlhood, and with a patriotic commitment to the nation. It was also an indoctrination rife with hypocrisy and contradiction. One of the first points of hypocrisy was the very term used to describe the prisoners — “evacuees” — suggesting that the imprisonment was for their own protection. Yet as one former prisoner noted, “If we were put there for our protection, why were the guns at the guard towers pointed inward, instead of outward?”

Girl Scout participation in the incarceration centers was very much in line with the history of the GSUSA. The arm of the Girl Scouts funding its program in Japanese American incarceration centers — the National Field Committee — had, up to this point, largely focused on bringing Girl Scouting to American Indian girls. Moreover, the fact that the Field Committee asked that monies be donated from the International Committee of the Juliette Low Memorial Fund also makes sense, as Japanese American girls were definitely understood by the national Girl Scout organization as “international,” not “domestic.” Girl Scouting could be brought to these Japanese (American) girls within this logic just as it was brought to the Chinese (American) girls in New York City and what they called Spanish (American) girls in the Southeast. I place “American” in parentheses because Girl Scouting definitely saw all these ethnic groups — Chinese, Japanese, Latina — as the foreigner within national boundaries. Working with the US government to create Girl Scout troops in incarceration centers also connected to the way the organization saw its mission as lending a helping hand and bringing an outlook and way of life designed to build character and health. As an institution it would legitimate and make sense of its work with incarcerated Nikkei girls as outreach and assistance, just as it had construed its forays into American Indian boarding schools as civilizing and uplift.

Girl Scouting asked girls to feel loyal and to perform loyalty to a country that was imprisoning them. In both its philosophy and its programming, the Girl Scouts was at heart a patriotic endeavor, and this was drilled into scouts in the camps. Eva Koyama, a young girl imprisoned at Minidoka, in Idaho, tells her father about joining the Girl Scouts, adding, “Here is the Girl Scout Oath”:

On my honor, I will try

To do my duty to God and my country

To help other people at all times

To obey the Girl Scout laws.

Duty to God and to country are in the same line, given equal weight, so for the imprisoned who felt it was constantly necessary to try to prove their loyalty to the United States, visible evidence of patriotism was very useful. Interestingly, both the visual and the written archival records of the incarceration centers provide many examples of Girl Scouts doing patriotic things. We learn about Girl Scouts planning Flag Day and Fourth of July events. We see them taking part in flag ceremonies, serving in bugle corps, and marching in parades. We learn that they raised money for veteran groups. For the girls and young women who were Girl Scouts, encouraged to take part in these motions of service and allegiance to country, the participation must have elicited extraordinarily conflicted feelings and mental dissonance as the incarceration centers and the Girl Scouts emphasized the necessity of embodying honor, respect, loyalty, and enthusiasm to the country that had imprisoned them and their families. Any examination of the Girl Scouts in the 20th century must emphasize how duplicitous the organization was in asking girls and women to demonstrate their “good citizenship” and their “patriotism” in a context where the United States had forcibly taken their homes and businesses, imprisoned them in often brutal conditions, and given them no particular reason to hope for their futures. It was a low moment for the Girl Scouts of the USA.

Emily Anderson, curator of the Coming of Age exhibit at the Japanese American National Museum, explained that for many families Girl Scouting was a particularly attractive organization before the war as it provided so much flexibility: The girls could be both “American” and “Japanese,” they could be both Buddhist and American, and they could be loyal to family and cultural traditions but also express their American patriotism and learn American cultural norms. Janet Sui Matarai Misaka, who was interviewed for the exhibit, provides a powerful example of the ways young women brought Girl Scouting into the incarceration centers. Ten years old when her family was forced to leave Mountain View, California, Misaka described herself as one of the “first Japanese Americans to join the troop in Mountain View,” a Brownie troop that was all white. With her mom’s help, she even won the cookie sale contest for the entire council. Movingly, she brought her Girl Scout Handbook with her to the camps; this detail really stands out, considering how little her family was able to bring and how difficult their relocation was. First they had to move to Santa Anita Assembly Center, a racetrack where she and her family were forced to live in converted horse stalls, and then to Heart Mountain in Wyoming. Within a month of her landing in Santa Anita, adults in the assembly center had begun Girl Scouting. Misaka recounted that the adults “got everything going fast to keep us out of trouble.” At Heart Mountain she remembered going with her troop down to the river, where they made little stoves out of cans and cooked some treats. She remembers making a memory album and learning how to build a stool. And they repeated the Girl Scout Promise, something she could do basically by heart even over 60 years later: “On my honor, I will try to do my duty to God and my country, to help other people at all times, to obey the Girl Scout laws.” When she finished reciting the Promise during the interview with Anderson, she started laughing wistfully and then reflected on the irony of her and other girls’ experiences with the Girl Scouts while imprisoned: “Well, we did all that. That’s what we did. We followed the Girl Scouts to the end.”

Toward the end of the war, government officials began a policy of moving people out of the incarceration centers to communities across the United States, in areas far from the West Coast. They turned to young women they identified as “exemplary” to safely serve as ambassadors throughout the country. These young women often went alone or in very small groups, as the point of resettlement was to break up what the government saw as a dangerous concentration of Japanese communities on the West Coast. Here, too, the Girl Scouts became involved, promising to have the various Girl Scou committees in the camps write to the councils where the girls and young women were moving, to encourage local troops to get in touch with and welcome the newcomers. The policy never seems to have been enacted in full, however, as the archival record includes statement after statement from the national board that the GSUSA will help resettle Japanese American girls, but there is no evidence that the GSUSA actually did it or that regional councils or local troops welcomed any of the girls. Before the war, the troops in California were largely segregated by ethnicity and class. After the war, however, GSUSA seemed particularly uninterested in creating any new troops for Japanese American girls, allowing only for the “possible assimilation of individual Girl Scouts.” This may seem progressive, as it would likely mean Nikkei girls integrating into already existing white, Black, and Mexican American troops, but it was probably more about ensuring that Nikkei communities did not reconstitute themselves after the war and instead dissolved into the nation.

Apparently, however, despite whatever publicity and letters the Girl Scout National Headquarters sent, local councils did not always welcome those who returned from the camps. A particularly painful example of this comes from Sally Kitano, who moved back to Bainbridge Island, Washington, after she and her family were imprisoned at the Manzanar concentration camp. She recalled:

When I got back to the island, a lot of the kids were, belonged to the Rainbow Girls. And that was, that was the thing to belong to. Okay, and then the other thing was joining the Girl Scouts. ’Cause I was in the scouting program before the war. And so I went up to the lady who ran the scouting program and I said, “Can I get back into the scouting program?” And she said, “Well, the kids are too far advanced now so I don’t think that you would fit in.” And I says, “Okay.” I mean, I accepted it. I was disappointed, very disappointed, but I said, “Okay. I understand that.” And then, but it wasn’t too long after that I found out that anybody can go join the Girl Scouts at any time.

After Kitano shares that she never rejoined the Girl Scouts, the interviewer asks her if any Japanese Americans joined. “Not at that time, no,” she answers. After which she adds, “I remember Remo, my classmate, said, ‘Well, let me see what I can do.’ You know, so she, so she had her mother call headquarters. And they said no, Japanese are not accepted. And that’s when I practically broke down and cried, ’cause I couldn’t get into anything. That was, that really hurt, I think.”

From Intrepid Girls: The Complicated History of the Girl Scouts of the USA by Amy Erdman Farrell. Copyright © 2025 by Amy Erdman Farrell. Used by permission of The University of North Carolina Press