An Attempt to Defeat Constitutional Order

Conservatives in South Carolina first attempted to defeat the state’s new post-Civil War constitution by appealing to the federal government they had fought three years prior. A petition was submitted to Congress, describing the new constitution as “the work of Northern adventurers, Southern renegades, and ignorant negroes” and claiming that “not one percentum of the white population of the State approves it, and not two percentum of the negroes who voted for its adoption know any more than a dog, horse, or cat, what his act of voting implied.” Conservatives complained that “there seems to be a studied desire throughout all the provisions of this most infamous Constitution, to degrade the white race and elevate the black race, to force upon us social as well as political equality, and bring about an amalgamation of the races.” They ended the petition with a warning: “The white people of our State will never quietly submit to negro rule.”

Congress refused conservative entreaties. But conservatives persisted in their fight. To prevent Black people and Republicans from prevailing in the first elections after the constitution, many turned to coercion, intimidation, and violence. In testimony before a state legislative committee investigating a disputed election, one South Carolinian said that employers had resolved not to employ any man who voted Republican. This was a smart strategy as many former slaves still relied on contracts with their former masters to earn a living. Slaveholders had exploited Black labor to build their wealth, and then used that wealth to build white political power.

Conservatives also used the legal system. One former slave was arrested and held without trial. Authorities released him when he agreed to vote Democrat. Sometimes, conservatives resorted to even more direct methods. In the spring of 1868, the Ku Klux Klan appeared in South Carolina for the first time, and worked to win the 1868 election for conservatives. After years of being denied a voice in the political process, Richard Johnson was excited to vote. But the night before the election, “the Ku Klux came through our plantation, and said if any of the colored people went to the polls the next day to vote, that they would kill the last one of them.” Some Black men on the plantation were so determined to vote that they still turned up at the polls. But several decided not to vote at the last minute because “the Democrats had liquor at the box upstairs and were drinking and going on in such a manner that the colored people were afraid to go up.” Eli Moragne was one of them. The day before the election, the Klan broke into his home, dragged him outside, stripped him naked, and then whipped him. He showed up despite the experience but was told that if he “voted the Radical ticket [he] would vote it over a dead body.” Armed white men stood between him and the ballot box.

Sometimes, Democrats engaged in violence without bothering to wear their Klan robes. William Tolbert, a Democrat who helped murder a Black Republican, observed that “committees were appointed, which met in secret, and they appointed men to patrol in each different neighborhood.” This was done “to find out where the negroes were holding Union leagues.” They had instructions to “break them up, kill the leaders, fire into them, and kill the leaders if they could.” Committees were supposed to take ballots from Republicans and kill those who resisted. Republicans did resist because Tolbert described a scene where one Republican had been shot dead and others had fled. The violence was effective. At one precinct, Tolbert would ordinarily have expected between four and five hundred Black men to vote, but Democratic committee members in the area only allowed two Black men to vote before they started shooting. There were similar drops in Black turnout across the state. For example, in Abbeville County, around 4,200 Black men were registered voters, but only 800 actually voted in 1868’s fall elections.

Republicans won the governorship and control of the legislature. But Democrats and conservatives saw that violence could be effective.

State authorities did try to respond. Amid Klan violence sweeping the state, Governor Robert Scott signed a bill authorizing a state militia. However, most whites refused to serve, a trend that became especially pronounced when Governor Scott rejected all-white militia companies offered by former rebels. In the end, as many as 100,000 men, mostly Black, joined by the fall of 1870. They often wielded state-of-the-art weapons such as Winchester rifles. White newspapers spread conspiracy theories about the militia. For example, after describing the militia sent to Edgefield as “the Corps d’Afrique,” the Charleston Daily Courier claimed that it had come to the town to commence “the arrest of citizens on trumped up charges of being ‘rebel bushwackers,’” and “‘members of the Ku Klux Klan.’” It then suggested that the militia had tortured an innocent white man into admitting that he was a “bushwacker.” Two things appear to have been truly offensive about Black militia units. First, they inspired pride among Black people. The paper complained that when a Black militia unit went to Edgefield, “the negroes of Edgefield became exceedingly jubilant, and determined to congratulate the colored soldiers on their great victory.” Second, the militia gave Black men another economic option besides relying on their former masters. As the paper lamented, “Among the numerous evils which have resulted to the people of Edgefield from this invasion of the county by the negro militia, has been the desertion of the fields by the negro laborers.”

Violence between Black militia units and white people erupted in Laurens County right after the 1870 election. After a gun discharged during a fight between a police officer and a citizen, a white mob began shooting at militia in the town. Several Black men and a few white men died during the fighting and in the subsequent upheaval. One of them was Wade Perrin, a Black legislator. White men caught up to him, ordered him to dance, sing, pray, and then run away. While he was running, they shot him in the back. Between 2,000 and 2,500 armed white men occupied the town. They had confiscated militia weapons from the armory. Two different stories developed about what had caused the violence. The Daily Phoenix blamed Black people. In the months before the 1870 election, the paper reported, “the white people had been subjected to an organized system of disparagement, abuse, and threats of violence to person and property, which had produced that feverish state of feeling incident to a deep sense of outrage and injustice.” Black people had allegedly become so unruly that “for weeks, whole families had not undressed for bed, so great was the apprehension of midnight negro risings, burnings and butcheries.”

The South Carolina Republican, however, claimed that a white man deliberately attacked a policeman to provoke him into firing so they would have an excuse to shoot. This must have been a premeditated plot because “it was not three minutes after the first shot was fired before a line of white men had formed across the public square … The white men came from every direction, out of the stores, the courthouse, and every other place, and what appears very singular is that every one was fully armed.” After the white men had fired on the militia, the paper reported that “white couriers were dispatched on every road, to rouse the people, so that by night at least one thousand men were scouring the countryside on horseback, and in little squads hunting up Radicals.” The incident attracted national media coverage. The New York Herald observed that “‘The War of the Races’ in South Carolina did not end with the rebellion, but occasionally bursts forth with its wonted fury.”

Governor Scott declared martial law in four South Carolina counties. But he also ordered remaining militia weapons in Laurens County transferred to Columbia. Removing the weapons ensured that the militia couldn’t be a serious fighting force and made the martial law proclamation meaningless. A wave of Klan violence swept the state after Laurens. The violence diminished temporarily later in 1871, though there is disagreement about why. Some have suggested that aggressive federal measures were responsible.

In 1871, the federal government stationed more troops in the state and engaged in a thorough intelligence gathering operation to learn more about the Klan. Federal legislation authorized President Ulysses S. Grant to use the military to enforce the law and placed congressional elections under federal supervision. What became known as the Ku Klux Klan Act allowed Grant to suspend the writ of habeas corpus when he deemed it necessary. After considerable debate, Grant suspended the writ in nine South Carolina counties on October 17, 1871. Over the next months, federal authorities arrested thousands of men for allegedly participating in the Klan and secured dozens of convictions and guilty pleas. These efforts were enough for one historian to claim that “the limited steps taken by the Federal government were adequate to destroy” the Klan.

Indeed, Klan violence was lower for the end of 1871 and some of 1872 than it had been earlier. At the time, however, law enforcement officials themselves were skeptical about whether their efforts had been effective. One prosecutor even suggested that “orders were given” from unknown persons to end the violence “for the present” and that the Klan would simply “wait until the storms blew over” to “resume operations.” By the summer of 1872, Klan activity intensified, indicating that any benefits from federal intervention were limited.

Given the immense opposition it faced, South Carolina’s government made important achievements. The state greatly extended educational opportunities. In 1868, 400 schools served only 30,000 students. But by 1876, 2,776 schools served 123,035 students. The state also expanded the University of South Carolina, even providing 124 scholarships to help poor students with tuition.

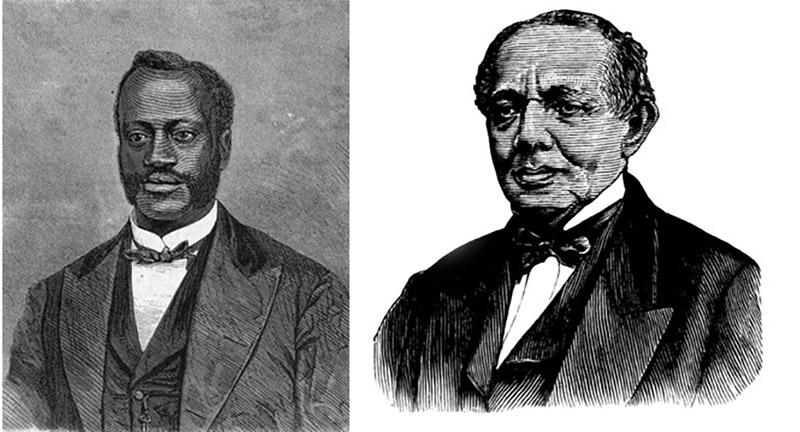

Perhaps most importantly, South Carolina saw unparalleled Black involvement in politics during Reconstruction. During these years, 315 Black men served in political office. Six served in Congress. Two Black men served as lieutenant governor. South Carolina was a place where a parent could take a son who had experienced chattel slavery just three years previously to the legislature, point to a majority of the members, and say, “that could be you one day.” The state that was the first to plunge the nation into Civil War because of its commitment to Black slavery was also the first to raise a Black man up to its supreme court. Jonathan Jasper Wright was born in Pennsylvania to free Black parents and managed to save enough money to attend college, a rare feat for both white and Black people in the era. He read law in his spare time while teaching to support himself. Upon passing the bar, he became the first Black lawyer in Pennsylvania. After the Civil War, he came to South Carolina to organize schools for freedmen. Wright had a neatly trimmed beard and mustache, and his somber eyes betrayed a young man who was in a hurry or a man weighed down with cares, or perhaps both.

Corruption marred all of the progress. In 1870, the Charleston Daily News wrote that “the South Carolina Legislature enjoys the reputation, both at home and abroad, of being one of the most corrupt legislative bodies in existence.” Corruption was so bad, the paper claimed, that “a remark frequently made among the white men in Columbia, Radicals and Democrats, was that two hundred thousand dollars, judiciously circulated among the legislators, would secure the passage of a bill repealing the Emancipation act, and putting all but colored legislators back in slavery.” The paper then asserted that there was an organization known as the forty thieves pillaging the treasury. The organization allegedly had a captain, three lieutenants, four sergeants, and twenty-eight privates. The group conspired to prevent the legislature from passing any “measure unless money was paid to the members of the organization.”

Although conservatives may have exaggerated corruption, it did plague South Carolina during Reconstruction. After John Patterson won election to the U.S. Senate, authorities arrested him when a legislator said he had voted for Patterson after receiving a bribe. Critics called Patterson “Honest John,” supposedly because he always made good on his promises to pay bribes. The legislature attempted to impeach Governor Scott for his behavior in issuing bonds. At the end of 1871, a Republican newspaper lamented that “1872 finds South Carolina financially in a bad way, with no one to blame but officials of our own party. This is a disagreeable statement to make, but it is the truth.” William Whipper, who had argued for enfranchising women at the 1868 constitutional convention, asserted Scott bribed legislators to escape impeachment.

All the corruption caused schisms in the Republican Party. Eventually Whipper, who would himself be accused of corruption, asserted, “It is my duty to dissolve my connection, not with the Republican Party, but with the men, who by dishonesty, demagogism and intrigue have defamed the name of Republicanism, and brought financial ruin upon the State.” Disgruntled Republicans joined the new Union Reform Party along with some Democrats. In the 1870 campaign, the party’s platform was “honesty against dishonesty — cheap, economical government against exorbitant taxation — reduction of public expenses against extravagant expenditure of the people’s money — responsibility of officials for the faithful discharge of their duties against irresponsibility, selfishness and greedy absorption of power.” The Reform Party failed to win the fall elections, though members alleged fraud and intimidation at the polls. Corruption in the Republican Party deprived it of unity precisely when it was most needed to overcome the massive resistance it faced.

Some observers even claimed that corruption led to the Klan violence against Black people and Republicans. But whatever else is true about the corruption in the South Carolina Republican Party, it does not explain the attempt to overthrow the constitutional order. We know this because conservatives and Democrats never gave the 1868 constitution or the Republican Party a chance. They schemed to prevent a constitutional convention in the first place, protested to federal authorities, and used terrorism, cold-blooded murder, and economic coercion to prevail in the 1868 general election. The reality is that, given their hostility to Black political advancement, they would have engaged in violence and attempted to defeat the new constitutional order even if every Republican official had been honest and efficient.

Excerpt adapted from Sedition: How America’s Constitutional Order Emerged from Violent Crisis by Marcus Alexander Gadson. Copyright © 2025 by New York University. Published by NYU Press.