The Daily Grail

Leisure, by Chao-Chen Yang, c. 1941. [Smithsonian American Art Museum]

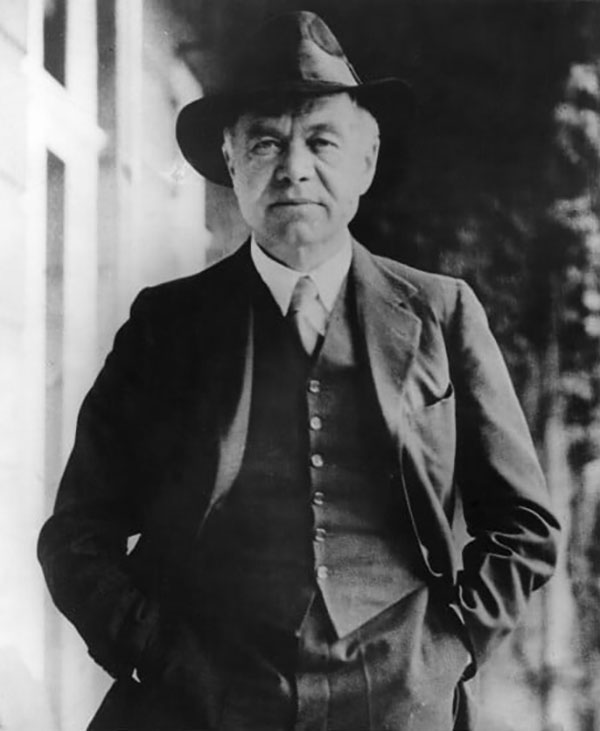

In the aftermath of the May 1929 general election, talk of tariffs bombarded the readers of the British newspapers the Daily and Sunday Express and Evening Standard. These newspapers were owned by Lord Beaverbrook, who had been trying to bring protectionism to the UK since moving there from Canada in 1910. He won a seat in Parliament on a protectionist platform in 1910, after deploying his immense wealth in service of North American-style populist tactics with more razzamatazz than was the norm in British politics. But popular enthusiasm for free trade remained a potent force in British politics through World War I and the postwar years, leaving Beaverbrook eager to create a constituency that did not quite exist by using the public-opinion weapons at his disposal.

British newspapers, which had historically catered to specific localities or interests, had, since the launch of the Daily Mail in 1896, been transitioning to a much broader distribution model. This created the possibility for publishers like Max Aitken — who became Baron Beaverbrook in 1917, a year after purchasing the Express and Evening Standard — to create popular support for policies that would primarily benefit either the economic or ideological goals of sections of the elite. Among them was “imperial preference,” which entailed a high tariff wall around the British Empire, and low tariffs within it. The policy’s goal was to bind the nations of the Empire — especially the Dominion nations of Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, with their large white settler populations — more closely together politically and culturally. While notionally an economic policy, imperial preference was therefore also a means of pursuing a deeper political and cultural project, and it drew upon and sought to reinvigorate notions of national and imperial greatness. Unfortunately for the Conservative Party politicians who typically advocated for it, imperial preference kept losing at the polls. A strong free-trade culture existed within Britain, and voters seemed wary about the effects of tariffs. Yet World War I had inflicted immense damage upon the British economy, which now faced much greater competition in world markets, an immense national debt, and the disastrous aftereffects of reinstating the gold standard after its wartime absence. This started to spread cracks in the formerly formidable edifice of free-trade support. Protectionist propaganda became increasingly difficult to avoid in the Express — and Beaverbrook was perhaps unfairly blamed by allies for not pushing tariffs hard enough in the run up to the 1929 election. Soon after, however, Beaverbrook’s decades-long campaign even had a catchy name and logo that helped prop up the mirage of protectionist popularity.

On July 2, 1929, the front page of the Express included a letter from Sir George McLaren, the European general manager of the Canadian Pacific Railway and an occasional contributor to the newspaper (though not framed as such), that responded to an earlier Beaverbrook headline asking, “Who Is for Empire”? The letter argued that saving the Empire must be the campaign’s driving force, that the movement must have “crusaders, but crusaders imperially led.” From that point on, Beaverbrook’s newspapers would take up the “Empire Crusade” for a policy known as Empire Free Trade — a form of imperial preference that included fully free trade within the Empire. The image of a crusading knight that adorns the Express masthead to this day first appeared during Beaverbrook’s Crusade. The intention of the campaign was to pressure the Conservative Party to implement a full program of imperial preference. Despite being a supporter of the policy, the leader of the Party, Stanley Baldwin, was not willing to implement it without an explicit mandate from the public, and had been unwilling to run on an imperial preference platform in the general election due to the defeats the Conservatives had suffered when doing so in 1906 and 1923. The Conservatives instead continued to pursue a much more limited form set of national protectionist policies, called “Safeguarding.” This was unacceptable to Beaverbrook.

Within three years, imperial preference was implemented. While the Empire Crusade cannot be credited as the only cause of this outcome, it did serve a critical role in helping to intensify a popular imperialism evident within Britain. It also importantly linked imperialism more firmly to tariffs, presenting imperial preference, rather than free trade, as the true expression of patriotic imperialism. It applied pressure on politicians at a pivotal moment. The multimedia, expansive strategy of the Crusade, along with its deployment of new technological and social innovations and use of patriotic and imperialist imagery and popular memory, were to become a media playbook that would be seen time and time again.

Beaverbrook aimed at making the campaign as broad in scope as possible to maximize the chance of reaching elites and the working classes, and maybe even some Labour and Liberal supporters, too. The 19th century Anti-Corn Law League was a source of inspiration; its pioneering use of combining lobbying of political elites with a popular social and media campaign had originally led to Britain becoming a free-trade nation. Beaverbrook tasked his newspaper staff with collecting information about it. He also made a wide variety of public appearances, where he addressed crowds with fiery rhetoric informed by his Presbyterian faith and reverence for 16th-century Scottish minister John Knox. Yet modern technology was used to support these public appearances. Beaverbrook would enter towns and cities across the UK via a fleet of sleek automobiles, and on occasion hired planes to drop pamphlets. He could also be accompanied on stage by a large box, which would make regular beeping noises to signify how often Britain was, he claimed, losing money to foreign industries. At each beep, Beaverbrook would intone that “the country has just spent another thousand pounds on imported food.”

He had learned from his media rivals that the appearance of having mass support was as important as actually having it. Beaverbrook published Crusader membership forms in his newspapers, waiving fees to encourage more of his readers to sign up. He also persuaded his fellow press baron, Lord Rothermere, owner of the Daily Mail, Daily Mirror, and a range of local newspapers, to support the Crusade, and together they launched the United Empire Party to run its candidates in by-elections.

Advertising in British newspapers had long been suffused with a patriotic-imperialist aesthetic, and Beaverbrook and Rothermere merged the advertising of their political campaign with the politics of their advertising campaigns. An article from the Express’ editorial department on June 27, 1930, noted that nine out of ten people, when asked if they agreed that purchasing British goods stimulated British trade would answer yes, but “merely believing in a precept is not enough. It must be practiced.” This article was surrounded by a range of advertisements bedecked in patriotic-imperialist symbols and language, from the Ossi-Vibro, a “British invention” to combat deafness, to Bermaline Bread, staking its claim as “the real Empire Loaf.”

Housewives, seen as controlling family purse strings, were also a primary target. It was women’s duty to “buy Empire.” This, they were told, would improve the health not only of the Empire, but also of their own families, who would benefit from superior Empire produce.

The highpoint of such efforts came with the launch of the aforementioned “Empire loaf,” a campaign within a campaign, which reused a concept originally from the Tariff Reform movement of the Edwardian era. In both the original case and the Crusade, the Empire Loaf was sold at a wide variety of larger and smaller business, and, as an Express article in May 1930 explained, it was “milled entirely from British and Empire wheat.” While free traders extolled cheaper bread prices made possible by the importation of wheat unimpeded by tariffs, Crusaders maintained that the higher priced loaf contained healthier ingredients and supported the Empire. Department store impresario Harry Gordon Selfridge explained in the Express that by selling the Empire Loaf, “we are following not only a wise national policy, but, above all, sound business principles.” Harrods made “the Empire Loaf the outstanding feature of their Bakery Week,” as announced by an advert in the Express on May 12, 1930. It was claimed elsewhere in the newspaper that the bread would become a “standard item of diet in every healthy British home.”

.webp.png)

Beaverbrook attempted to turn his campaign into a fully-fledged social movement. He set up an organization called the Young Crusaders, partly modeled on the Boy Scouts, and regularly invited them to camp on the grounds of his manor house, Cherkley. The Crusade also organized music nights, combining old-fashioned mass singalongs of anthems dedicated to imperial heroes with jazz. As an Express report about the Young Crusader event on April 16, 1930, noted: “One has a sentimental attachment for the old songs and the old tunes, but, for all their lilt, and their melody, they do not move to the pace which this postwar life demands.” Membership in the Young Crusaders consisted largely of the sons and daughters of elites. The April 1930 event was noted to have been attended by an audience of 3,000 under-25s, “most of them well known in London society.”

Beaverbrook also looked to Germany for inspiration. One of his models was a youth movement called the Wandervogel. Another was the Nazi Party. While he never had any relationship with or sympathies for the Nazis, unlike Rothermere, Beaverbrook was quite interested in their propaganda techniques. He tasked the Express Berlin correspondent, Denis Sefton Delmer, with sending information about Hitler’s personal methods of engaging crowds and cultivating a sense of charisma. According to Beaverbrook’s close confidante and factotum, Robert Bruce Lockhart, Beaverbrook even began to ape Hitler by “walking straight out on to the stage without an introduction and without a chairman!”

Free-trade supporters, meanwhile, generally stuck to their traditional forms of rhetoric, methods, and institutions, which had served them so well in decades prior. This included various liberal newspapers, like the Daily News and the Daily Chronicle (which merged in 1930) the Manchester Guardian, and pressure groups like the Free Trade Union and the Cobden League. But by the onset of the 1930s, such efforts were increasingly moribund, and the old arguments did not carry the same weight. That Britain’s preeminent position could be ensured by adherence to free trade was belied by the nation’s financial difficulties — and the booming economy of the U.S. and a seemingly resurgent Germany. The structural unemployment of the interwar period, when millions remained without work for years, undermined the notion that free trade would bring prosperity for all social classes.

The sternest opposition to the Crusade came from the main target of its pressure: former prime minister Stanley Baldwin — supporter of imperial preference and hater of press barons — who remained leader of the Conservative Party. He was determined to keep the party free of influence from unelected media owners. Matters came to a head in March 1931 at the Westminster St. George by-election, where the United Empire Party candidate, Ernest Petter, stood against the Conservative Party’s candidate, Duff Cooper. On the eve of the election, Baldwin delivered a speech that has become the most famous rebuke of the press in British history, saying: “What the proprietorship of these papers is aiming at is power, and power without responsibility — the prerogative of the harlot throughout the ages.” The following day, Cooper was victorious.

Many commentators would later claim this as the moment the Crusade ended, and use it as a case study about the limits of press power. But this is a misleading narrative. Westminster St. George was a very atypical constituency, home to the wealthy upper-class readers of The Times and the Morning Post, the leading press supporters of Baldwin.

Across the rest of southeast England, where the papers of the press barons had their highest circulations and the Crusade’s events were most active, imperial preference enjoyed a high level of support, which had been growing ever since the original Tariff Reform movement of Joseph Chamberlain. Baldwin had earlier contemplated resigning as party leader due to the amount of criticism directed at him and local Conservative Associations over their failure to wholeheartedly back the policy. More generally, the longer mobilization of large parts of the press in support of the issue since the Edwardian period and the more intense campaign waged by the Crusade helped shift the terms of the national debate, forcing free trade into retreat. Free-trade support had become the preserve mainly of a range of newspapers and journals that had far lower circulations than those of the protectionist press. The Manchester Guardian, an important liberal title with a relatively small readership, bullishly called for an election on the issue of free trade and protectionism in response to the publication of Beaverbrook’s pamphlet Empire Free Trade in October 1929. Yet in private, the newspaper’s editor, Ted Scott, admitted even he had “very great difficulty in accepting the theoretical Free Trade case with the confidence I felt in 1906.” More generally, the civil society network of pressure groups and unions which had once served as a bulwark of free trade support was much diminished by 1930; there were fewer pressure groups which generally had fewer members, and sections of the union movement had themselves turned towards protectionism.

In the aftermath of the 1931 European financial crisis, the gold standard was finally dropped, and a new national government dominated by Conservatives was formed. Beaverbrook fell in line and did not attack the new government, though his newspapers continued to promote Empire Free Trade. Stanley Baldwin was a key player in the national government, and, somewhat ironically, was now able to push for imperial preference. Despite having opposed the press barons, he benefited from the way their campaign had helped shift perceptions over the tariff issue. By the Imperial Economic Conference of 1932 in Ottawa, the latest in a long-running series of conferences aimed at cultivating cooperation between the governments of the self-governing colonies of the Empire, imperial preference, now seen as politically feasible, was finally implemented.

It may not have been the full Empire Free Trade called for by Beaverbrook, but his broader goal was achieved. This was the culmination of three decades of protectionist campaigning by a large swath of the British press, with the Empire Crusade, and its intense press campaign and social initiatives, serving as a capstone. The Crusade by itself did not cause this change, nor can it be attributed to the media more generally — the Great Slump that had blighted the nation through the 1920s and more recent Great Depression loomed large, changing people’s perceptions of the economy without much prompting. But the press campaign bolstered and reinforced popular imperial enthusiasm and linked it to protectionism, entrenched and intensified support for the cause among the demographics where the newspapers had most purchase, and helped present an image of its widespread popularity.

Well into the post-World War II period, when the Empire began to dissolve, Beaverbrook would champion the patriotic-imperialist cause and Empire Free Trade. While his media efforts could not halt decolonization, they nevertheless still left an imprint on British politics and culture, and popular conceptions of Britishness. The nationalism and imperial nostalgia that contributed to Brexit resonate with the rhetoric of the early-20th century popular press — including the discourse around the Empire Crusade. More recently, we are hearing echoes of the crusade from the other side of the Atlantic, as the selling of Donald Trump’s tariff policies subsumes highly technical economic and political considerations to broader notions of identity and nostalgic visions of past national greatness.