Starting with a Question

On a Clio campus history tour at Marshall University, alumni share the history behind each building and landmark.

The piece below is the first entry in a series we’re debuting this fall, letting public historians discuss their work at a time when funding for it is growing scarce, and opportunities abound for bad history to circulate. These pieces will discuss critical questions in the field of public history, such as: How do you make history visible and show people how to see it as part of the world they live in? What strategies have proven successful, and what aspects of “industry practice” have been less helpful? How do you challenge calcified ideas about history that are off-kilter or incomplete? Are you a public history practitioner with insights to share? Consider sending us a pitch.

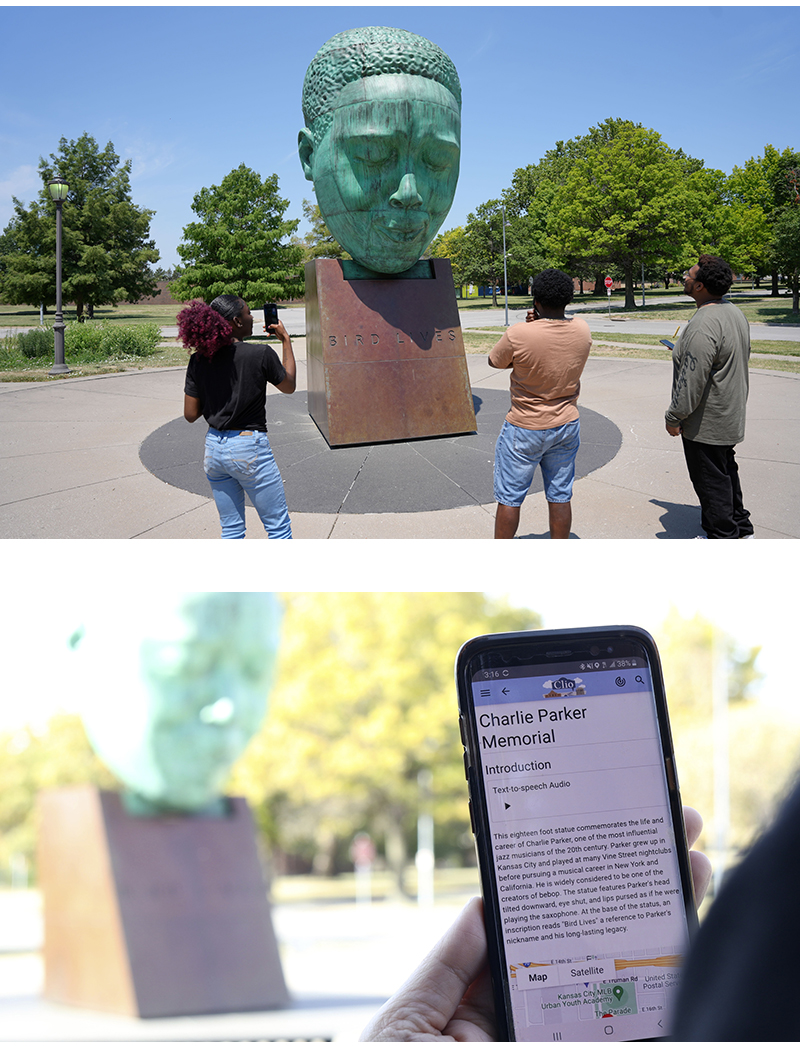

If historians and librarians designed the technology of our era, how might “smart” devices work to make us smarter and more connected? For the last 12 years, that’s been the question guiding Clio, a pedagogical tool that doubles as a travel app to get people hooked on learning history. Users can see landmarks near their location and then learn about these places through short articles authored by students, scholars, museum professionals, and local historical societies. They can also follow a walking or driving tour or simply turn on the location-based notifications in the app to learn about the history that surrounds them. More than a thousand organizations and 500 professors have worked with staff and students to author the growing library of over 40,000 articles for historic buildings, markers, monuments, and other landmarks in Clio. There are also more than 1,700 walking tours and trails across the United States and beyond that combine individual articles for landmarks along with “contributing entries” that live within a specific tour or trail to offer another layer of interpretation beyond landmarks.

Clio started as a local history project in West Virginia. With encouragement from other historians, I made it possible for professors to create and edit entries and tours with their students, with each entry crediting the student, professor, and university. We named the website and mobile app in honor of the ancient muse of history, and we’re constantly improving both as donations and grants allow. In fall 2025, we’re adding support for multiple languages along with more options for in-person navigation and “city pages” that offer compilations of highlights for residents and visitors.

The result is that Clio makes it possible to travel through space and learn about the history behind the landmarks you pass. Most Clio entries are text-based, but some embed narrators and oral history clips. All entries cite their sources, and link out to related books, articles, websites, and media. In recent years, Clio has grown to include narrated hiking trails, immersive virtual tours of museums, driving trails, and interpretive tours along public transportation routes. In a way, you can think of Clio as a digital overlay of our world that connects our natural curiosity about the things around us to the expertise of historians. Many commercial platforms offer these services for one organization and in one location. Clio works nationwide, is nonprofit, and free for everyone to use.

I built Clio to share the joy of discovery and learning, both in familiar and faraway places. I think that project has resonated with the public we serve, because it connects our sense of place with knowledge of the past. Since each entry includes sources and links, it also demonstrates the process of history and promotes the work of our colleagues.

The idea that sparked Clio was born in 2014. I had been teaching at Marshall University for three years when it hit me that the lecture-and-exam format I was using, as beneficial as it was, also reinforced the idea that history was a series of answers. I wanted to show students that it was also an active process. I asked each of them to research a place that mattered to them. I told them we would publish their work on a local history website, and then met with each student three times. The difference between their first and final drafts showed that they had learned the process of doing history. They clearly explained how each new source and perspective challenged their conclusions, which were only as strong as their evidence. Their writing steadily improved as they discovered and incorporated more sources and perspectives, learning about the provisional nature of knowledge along the way. As they polished their final work, students were saying things like “I can’t publish this yet because the third person I interviewed told me something different from the other two,” or “I’m still trying to figure out…”

In a world where AI can generate essay responses, this kind of project-based learning has been refreshing. And in a world where so many start with an answer and then select evidence to support that conclusion, Clio encourages students to start with a question and follow a process that combines hard work and humility to create something worth sharing with others. When students author Clio entries with an understanding that their work will be published, they approach their work as aspiring professionals. More than 600 other college courses have used Clio over the last decade, and nearly 8,000 articles have been authored by students with the help of their professors.

For a history app to be worthy of space on someone’s phone, it must work everywhere, be simple to use, and cover all topics. We’re still missing quite a bit, but the project gets a little better each day. An average of 200 new articles are added each month, along with plenty of revisions and updates.

If you care about people, you go where they are. I think that’s why Clio works — every entry starts with a short introduction that seeks to address the initial curiosity of readers about places and markers near them. After learning when a building was created or why a historical marker was dedicated, the reader goes on the “backstory,” section that offers more details and context. While many historical markers only have room for a few dozen words, Clio entries can go further with text, audio, and photos.

An entry about a historical marker in Burlingame, Kansas, offers a good example. The Burlingame marker is nearly identical to over a hundred others along the Santa Fe Trail, but in Clio, readers learn that the marker was originally located in the center of town, where a Free State fort stood during the Civil War. The backstory shares the 1858 decision to rename the town to honor the abolitionist Anson Burlingame, who was challenged to a duel by South Carolina Rep. Preston Brooks after Brooks caned Massachusetts Sen. Charles Sumner in 1856. (The challenge was prompted by a speech Burlingame gave after the violence at the Capitol; the duel, set to take place at Niagara Falls, was canceled after Brooks learned of the abolitionist’s marksmanship.) Read on, and you will learn how the Daughters of the American Revolution studied the route of the Trail, and why this marker was dedicated in honor of one of those women shortly after her passing.

Since Clio does not show ads or monetize traffic, the platform is built to inform the public and promote the work of historians. The current library of 40,000 Clio entries includes links to over 200,000 related books, articles, websites, and digital projects. If someone clicks away from Clio and ends up buying a book about a topic they just discovered, that’s a win. Even better, hundreds of users have shared fun stories of “Clio moments” where their family made a side journey because someone in the car —hopefully the kids — were using the app or website.

I’ve loved visiting some of the campuses and communities that have used Clio. There’s a wonderful civil rights tour in Huntsville, Alabama, and a fascinating entry about women’s history on MIT’s campus. There are walking tours of sacred Native American sites narrated by tribal members, and explanations of downtown buildings in many cities delivered by local residents. There are more than 1,000 entries for landmarks in New York City, thanks to organizations, faculty, and librarians at New York University and other institutions. There are also driving tours along country roads and audio tours that follow rail lines. There are hiking trail tours that offer a blend of nature and history, narrated walks along park trails, and tours of the insides of public buildings that are narrated by local historians and artists who reveal the inspiration behind murals.

One of the most unique aspects of Clio is that it connects people to histories they are unlikely to discover via search algorithms and AI platforms that base results on user input, web traffic, and reviews. Every entry in Clio, from the Washington Monument to tiny local museums, has the same footprint. Searching by location allows for the serendipity of discovering places and topics you didn’t already know you wanted to explore. If you only have an hour to explore a city between conference sessions, you usually just end up walking around your hotel. If you share your location in Clio, that walk could reveal the stories behind a dozen markers, monuments, murals, and historic buildings, covering topics ranging from a civil rights sit-in to a tragic hotel collapse that changed building codes.

I still think of Clio primarily as a pedagogical project that views history as a process that starts with questions and a search for evidence. Clio users also benefit from this process, because profound things happen when people become more aware and connected to the history around us. We become more present, more curious, and more aware of what we have not yet learned. Our phones often serve as mirrors, reflecting and validating what we already know and believe. But maybe they can become windows, helping us to see the perspectives and knowledge of others.