If the Slipper Doesn’t Fit

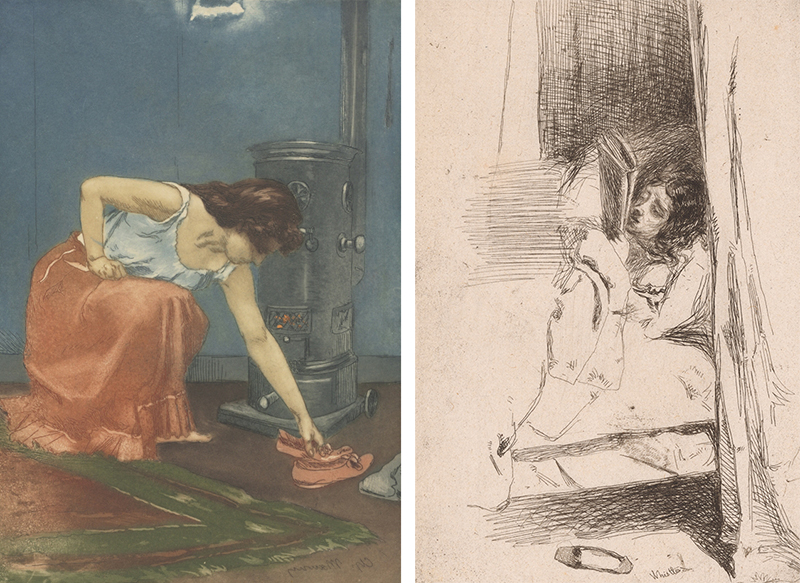

Cinderella Tries on the Slipper, by Millikin and Lawley, c. 1890. [The J. Paul Getty Museum]

On the night of March 10, 1948, the main building of Highland Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina, mysteriously caught fire. The hospital kitchen was found aflame around 11:35 p.m. While staff woke and evacuated most patients, smoke and flames rose through the dumbwaiters, preventing rescue efforts on the upper floors. Attempts to enter the hospital from the outside were stymied by windows reinforced to discourage patient escapes. Steel chains had to be cut before anyone could enter or exit from them. The blaze could have been caused by an overheated coffee urn, or by Willie Mae Hall, who supervised the psychiatric patients within. She oscillated between claiming she’d done it and being unsure that she did, and was ultimately admitted to a psychiatric hospital herself. No definitive cause was established and no crimes were charged.

Nine women died in the Highland Hospital fire. One of them was Zelda Fitzgerald, an on-and-off patient there since 1936 due to what was diagnosed as schizophrenia. On that night, she was recovering from insulin shock therapy on the hospital’s top floor. She had fallen far from the public eye at that point, eight years after her husband F. Scott Fitzgerald’s death; newspapers reporting on the fire list her name among the other victims’ with little to no fanfare. Hers was one of the last bodies to be found under the rubble. Many of the sources you’ll find claim that the remains, burned beyond recognition, were only identified by the slipper found underneath them.

The earliest record of this slipper seems to be Nancy Milford’s 1970 biography, Zelda, often cited as the authoritative biography of Zelda Fitzgerald. It is an extremely well-researched book that began as a master’s thesis, with citations for almost every line. This makes it strange that one of its last sentences lacks a proper one: “Her body was identified by a charred slipper lying beneath it.” Flipping to the end of the “Notes and Sources” section of the biography, the only additional information is: “It was further identified by recent dental work.”

Where did this detail come from? As a budding scholar who has learned to be very meticulous with my citations, I was surprised and confused by the lack of a paper trail. When I first began looking into the slipper, I was trying to write a final paper about it for a class on material cultures. I’d remembered reading somewhere that the slipper was monogrammed and a gift from Scott. It seemed like a captivating object that I could consider alongside ongoing public fascination with the Fitzgerald romance. That’s what I wanted to write my paper on, at least, until I hit a dead end just days before my annotated bibliography was due.

According to Milford, the slipper was only charred: her account lacks the specificity that I remembered. Looking through other books and searching scholarly databases, a slipper matching Milford’s description, sometimes word-for-word, appeared occasionally. More often it wasn’t mentioned at all, attributing identification to the dental records. As I lost hope, I turned to Google. Even if I couldn’t find something suitable for my paper, I still wanted to know where I’d received my version of the story.

In a 1989 article from Blue Ridge Country magazine titled “The Tragic Death of Zelda Fitzgerald,” the slipper is sexy red leather, “a symbol of the hamartia — the fatal flaw — of [Zelda’s] own personal Greek Tragedy.” According to the website of Lee Smith, who wrote a novel featuring Zelda as a character in 2013, it was a “charred ballet slipper — for the brilliant Zelda was still a talented dancer and choreographer as well as a writer and a visual artist.” A 2021 article on the website Grunge claims there were two slippers, and that they were “the iconic red slippers she always wore.” Each article lacks any clue as to where its unique description comes from, but in their respective accounts, these well-described shoes all serve a narrative purpose.

In each example, the slipper shapeshifts to serve its writer’s version of Zelda: doomed flapper, persistent dancer, fashionable heroine. Even for my own paper, the slipper was just the door through which I planned to explore a different topic. When I couldn’t find proof of my own version of the slipper — or even proof that any slipper existed at all — it no longer served the story I wanted to tell. Upon realizing I had to find a new paper topic, Zelda’s slipper began to symbolize something new for me, well-phrased by scholar Anca Peiu in her continuation of the slipper story: a “final frivolous question mark.” Why is this little slipper so popular, despite seeming to spring into existence 20 years after its owner’s death?

In 1979, journalist Perry Deane Young questioned the reliability of Milford’s slipper story, saying it “seems unlikely considering the intensity of the blaze.” Her mention of the dental records, despite being relegated to the outskirts of the biography, seems to have been more accurate. Zelda’s funeral director noted in his papers just days after the fire that “Mrs. Zelda Fitzgerald’s body has been positively identified by dental work.” We’ll probably never know why Milford included the slipper in her biography — she died in 2022 without addressing it — but its popularity shows that contributors to Zelda’s mythology find it a fitting detail.

Slipper or no slipper, Milford’s biography is still one of, if not the, most important about Zelda Fitzgerald. It played a unique role in redefining Zelda to account for her own creative output — her art, short stories, play, and 1932 novel Save Me the Waltz — much of which was ignored or demeaned in previous cycles of Fitzgerald obsession.

Following the release of the first F. Scott Fitzgerald biography in 1951, Arthur Mizener’s The Far Side of Paradise, the dazzling literary couple became more popular than they had been within their lifetimes, and Zelda’s image took its pre-slipper shape. Journalists Tex McCrary and Jinx Falkenburg noted in a 1951 interview with Mizener that Zelda “had been a fine painter, a fine writer, but never great at either” and posit that jealousy of Scott led to her madness. She was often painted as an antagonist — a narrative furthered not only by these early biographies of her husband but also by the memoirs and correspondences of famous friends like Ernest Hemingway. “If he could write a book as fine as The Great Gatsby I was sure that he could write an even better one,” Hemingway wrote in his posthumously-released memoir, A Moveable Feast. “I did not know Zelda yet, and so I did not know the terrible odds that were against him.” When Zelda was considered alone, it was often as the final boss of flapper-dom, such as in a 1960 fashion show review in which a model’s bobbed hair is described as “shingled shorter than Zelda Fitzgerald’s at the height of the Twenties.”

While Zelda continues to be tacked on to discussions of her husband or invoked as the prototypical flapper, these depictions became less common after Milford’s 1970 book introduced a talented and misunderstood Zelda compelling enough to stand on her own. Much of the critical discussion of Zelda since then has been dedicated to separating her legacy from Scott’s. More Zelda biographies, nearly all written by women, entered the scene in the 1990s and 2000s. Sally Cline’s Zelda Fitzgerald: Her Voice in Paradise served as a turning point in 2003 and reversed the antagonistic dynamic present in earlier characterizations of the Fitzgerald relationship, asserting that Scott stifled Zelda’s writing by plagiarizing her work and organizing her continued hospitalization for schizophrenia.

Whether husband plagiarized wife remains a contentious debate in Fitzgerald studies, but no one can deny Zelda’s profound influence on Scott’s fiction. As his muse, much of her own speech flows from his characters’ lips. Take, for example, the iconic Daisy Buchanan quote from The Great Gatsby, “I hope she’ll be a fool — that’s the best thing a girl can be in this world, a beautiful little fool.” It was inspired by the words he recorded Zelda uttering after their daughter’s birth. At least one excerpt from her diary was used in The Beautiful and Damned, and Nicole Diver, the domineering schizophrenic wife of the handsome and promising protagonist from the semi-autobiographical Tender Is the Night, is heavily inspired by her, including but not limited to her diagnosis: Scott even drew out a chart showing the parallels between his wife’s and his character’s cases. The green light at the end of Daisy Buchanan’s dock is one of the most iconic symbols in American literature, and it absorbs her character, morphing her into a glowing goal to reach toward rather than a living, breathing woman. If Daisy becomes a light, why would Zelda not become a slipper? Because of the blurred lines between Scott’s literary output and his own experiences, it makes sense that the ways his novels are read would shape how Zelda’s story is told.

A great proliferation of Zelda-related fiction came 90 years after Scott’s first novel was published. In Woody Allen’s 2011 film Midnight in Paris, Alison Pill as Zelda declares that her “real talent is drinking” in a sheer flapper-style dress and later is saved from jumping into the Seine by an anachronistic offer of Valium — not every recent portrayal is terribly concerned with rehabilitating her image. In 2013, the same year that Baz Luhrmann’s film adaptation of The Great Gatsby hit theaters, there was an eruption of books about Zelda: at least six novels from that year feature her as a primary character. Therese Anne Fowler’s Z (adapted into an Amazon drama series in 2017 with Christina Ricci as Zelda) allows her to tell her own story, in which she is held back from exercising her creative genius by Scott and a cast of male doctors. In Call Me Zelda, Erika Robuck uses a nurse character to explore the Fitzgeralds’ relationship. After Zelda entrusts her with a secret memoir, she uncovers Scott’s creative exploitation of his wife.

In the eyes of these writers, Zelda was called “crazy” for flouting societal norms or for straying too far from her status as Scott’s fruitful muse. But recent efforts to reclaim Zelda’s legacy run the risk of rehabilitating the historical figure beyond recognition. The specifics of Zelda’s schizophrenia are irrational and frightening, and many of the more distressing facts about it don’t appear in the kinds of articles her slipper pops up in, or in her many fictionalizations. In a letter from her first hospitalization in 1930, she apologized to Scott for being short with him with the prescient claim that, “I’m rather angry because people won’t let me be insane.” In 1929, she’d attempted to kill Scott and their young daughter, along with herself, in an automobile. During breakdowns, she was known to engage in coprophagia — the compulsive consumption of feces. Later in her life, she became a proponent of fascism, telling scholar Henry Dan Piper that she was joining as many fascist organizations as possible “to keep things from falling apart.”

In delving into unflattering specifics like these, one runs the risk of making a spectacle of her more dire moments. Yet they are also part of her historical character — and reliably documented. To claim that Zelda did not suffer from mental illness is to ignore not only her own words, but parts of her history that do not fit into a romanticized narrative of brilliance and oppression. Scholar Lauren Moffat put it perfectly in 2021, “To let her be what the historical record suggests she was — iconoclastic and apolitical, creative with psychosis, performative and sincere, defiant and dependent — demands that all bias, projection, and political wish-fulfilment be set aside. What is clear, and not only concerning her mental illness, is that Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald is difficult to define.”

The slipper myth has the potential to represent Zelda cleanly, to package her story more neatly than it unfolded. Years of illness and early shock therapy took their toll on Zelda’s personality and cognition, and so it would be satisfying to still hold on to a glimmer of what she once was and what many would rather remember her as. The belief that all of the moments of Zelda’s life tell her story, not just those with Scott in them, was central to Milford’s biography. Perhaps the slipper was a way for her to bring a beautiful past into a damned then-present, of exemplifying that all of a person can be true at once.

But the life that the single sentence took on in the years after is a reminder that history can easily be shaped to serve writers’ own agendas. It also illuminates the challenges around fairly depicting historical figures who we may not want to emulate. Narrative injustice was almost certainly inflicted upon Zelda in the years after her death. But correcting those injustices with stories we want to see, stories that ignore the full archive, only inflicts more harm upon her legacy. The slipper has become a vessel, ready for all comers to slip their own version of Zelda into. But a faithful representation of this enigmatic woman cannot be shoehorned into it. It is time for us to toss the charred piece of fabric aside and look more closely at Zelda herself.

What might she tell us? Perhaps something like what she told Scott when he expressed concern for her while she was in hospital: “Stop looking for solace: there isn’t any, and if there were life would be a baby affair.”