A Republic, if They Can Force It

Abbot Academy students with “Problems of Democracy” exhibit, 1938. [Digital Commonwealth, from the trustees of Phillips Academy] (CC BY-SA)

Amidst the widespread fallout from the 2024 presidential election, it hardly registered as news when Alabama’s state education board proposed new social studies standards for the first time in 14 years. In a moment when red states were rushing to ban “critical race theory” and “divisive concepts,” Alabama’s new guidelines for K-12 education were praised by Democratic members of the State Board of Education and aroused little public criticism. Few observers seemed to realize that profoundly undemocratic language was buried in the fine print.

The state’s undermining of the fundamental principles of American government are first visible in the introduction to the 2024 Alabama Course of Study: Social Studies. It describes the purpose of education as giving students the “knowledge to uphold and enhance the constitutional republic to which they belong.” That term — “constitutional republic” — does not appear anywhere in Alabama’s existing standards, which use the term “constitutional democracy” instead. Nor is it included in the National Council for the Social Studies’ K-12 national standards, produced every few years by blue-ribbon panels of educators and educational policy experts, or the 1996 National Standards for History, funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the U.S. Department of Education. The latter guidelines state only that middle and high school students should be able to “explain how key principles in the Declaration of Independence grew in importance to become unifying ideas of American democracy.”

“Constitutional republic” is a term of wildly conflicting connotations. It was unknown in the founding era but is used by some to urge the importance of fealty to the framers’ original principles. Partisans on the Right have adopted the term as a means of justifying the expansion of executive and judicial power over that of state and federal legislatures, downplaying the founders’ commitment to popular democracy. Those on the Left have employed it to condemn those same moves. In the Trump era, uses of this term have multiplied and deepened to justify the dismantling of democratic norms and the rule of law itself.

America’s patriotic origin story of having emerged from a popular revolution against aristocratic tyranny, as well as Enlightenment principles that vested sovereignty in the people rather than a king, has been an obstacle to those who have mistrusted the wisdom of the crowd. Faced by the difficulty of defying the popular will while at the same time claiming to uphold core American ideals, elites latched onto a terminology that redefines America’s central Constitutional principle as its opposite — hiding that first line “We the People” behind the messy machinery of how laws are made and executed.

Framing America’s founders as being indifferent or hostile to democracy has ripple effects throughout the proposed Alabama social studies standards. There are ten content standards relating to the War for Independence and the origins of the American government. None of them mention that the patriots fought against monarchy and for a representative form of government. The word “democracy” is not to be found outside of classical Greece until students study World War II and are told to “compare totalitarianism and democracy.” Unmoored from an idea that their own nation was born in a struggle against dictatorship, Alabama students will have to satisfy at least five content requirements exploring “Russia’s struggle for democracy” and “the breakdown of democracy in Germany.” Only in the broad outline of best practices regarding “civic thinking” do Alabama standards link the U.S. and democracy, and then only weakly in encouraging students to “analyze the role of citizens in the United States political system, with attention to the various theories of democracy.”

Another spillover effect of the implicitly scornful attitude toward democracy is a bias in favor of the most undemocratic features of our political system. Alabama’s guidelines valorize the Electoral College, described as a system in which “candidates must appeal to a wide variety of states and develop coalitions in order to secure the electoral votes required to win the presidency.” This is profoundly ahistorical: no presidential candidates conducted (or even could imagine) such campaigns until nearly a century after the Constitution was written. No one justified the Electoral College in this way until the 20th century. The “constitutional republic” rallying cry also aims to discredit those elements of the Constitution that redefined citizenship, mandated legal equality, and forced states to extend the judicial protections passed after the Civil War. Conservatives who find these provisions inconvenient have tried to elevate the Constitution as it was ratified in 1788 above these later alterations by exalting the “original intent” of the founders, tip-toeing past the fact that the amendments guaranteeing birthright citizenship and voting rights are a part of the “Constitution,” too.

The phrase “constitutional republic” does not appear in the 34 volumes of the Journals of the Continental Congress. Judging by James Madison’s and others’ notes from the Constitutional Convention, it was not aired there either. Madison and Alexander Hamilton referred to America’s government as a “representative republic” in the Federalist Papers. John Adams called the United States as a “Democratical Republic” around the same time, both terms preserving a core element of democracy, but neither used them in the sense that conservatives have formulated “constitutional republic".

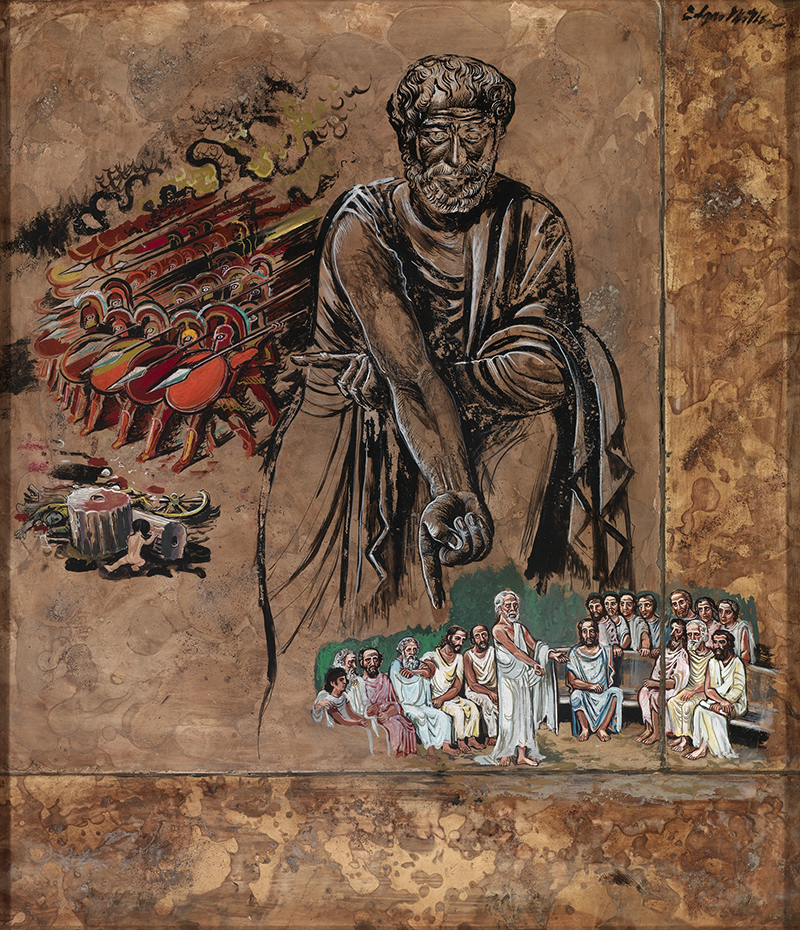

Conservatives are not wrong in suggesting that the founders preferred the term “republic” to “democracy,” but they misrepresent their heroes in claiming that they somehow saw the two terms as referring to different things — or worse, as being opposites. It is abundantly clear that the founders did not reject democracy in theory, though some were determined to cage it like a wild animal. Raised in classics and embracing the most liberal strains of the French and English Enlightenment, the most celebrated drafters of the Constitution understood that what defined a society was not who held office or who voted but who was ultimately sovereign: “We the People.” James Madison in Federalist 39 defined a republic as “a government which derives all its powers directly or indirectly from the great body of the people” by lawmakers who were “appointed, either directly or indirectly, by the people.” Or as Madison put it bluntly in Federalist 10: “The two great points of difference between a democracy and a republic are: first, the delegation of the government, in the latter, to a small number of citizens elected by the rest; secondly, the greater number of citizens, and greater sphere of country, over which the latter may be extended.” In other words, there was no difference of kind, only of mechanics.

John Adams may have been the only prominent founder to ever use the phrase “constitutional republic,” and he didn’t string those words together into a phrase until he had retired from public life. In 1807, he sent a cranky letter to historian Mercy Otis Warren complaining of her treatment of him in her History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution, confessing that he never thought the word “republic” meant anything.

The Word is So loose and indeffinite that Successive Predominant Factions will put Glosses and Constructions upon it as different as light and darkness, and if ever there should be a Civil War which Heaven forbid, the conquering General in all his Tryumphs may establish a Military Despotism and yet call it a constitutional Republic as Napoleon has already Set him the Example. The only Effect of it that I could ever See, is to deceive the People.

The term “constitutional republic” began to gain prominence in the 1820s to warn of the rise of an American demagogue. Reacting to the prospect of General Andrew Jackson becoming president, an 1824 letter to the editor published in a New Hampshire newspaper wondered “whether it is expedient to confer the highest offices in our government upon men distinguished merely for their military services. My own opinion upon the subject is, that when ever we are ready to take this step, we shall be quite ready for the next-viz. to convert our constitutional republic into a military despotism.” A decade later, South Carolina Rep. Francis Pickens, still incensed over the tariff policy that sparked the nullification crisis, railed against now-President Jackson on the floor of Congress in 1836, charging him with making constant appeals “to the people as one aggregate mass, all, all, announced, in language not to be mistaken, that the constitutional Republic of States was to be broken down, and that a simple democracy of brutal numbers, with an elective and unlimited monarch, was to be raised over the ruins.” Gov. Pickens later approved the bombardment of Fort Sumter.

For these men, “constitutional republic” referred to a government in which executive powers were restricted, or as one newspaper editor put it in 1839, “a Constitutional Republic of limited powers — equally opposed to Anarchy and to Despotism — to the rule of one man or the rule of a mob.” President John Tyler, defending his veto of a bill rechartering a national bank — a veto so unpopular it would get him thrown out of the Whig party — sent to Congress an 1841 veto message that claimed he was upholding his oath of office in blocking an unconstitutional law.

He must either exert the negative power intrusted to him by the Constitution chiefly for its own preservation ... or commit an act of gross moral turpitude. Mere regard to the will of a majority must not in a constitutional republic like ours control this sacred and solemn duty of a sworn officer.

In this sense, the term was related to the need for institutional safeguards against popular “passions” and “excess” that corrupted the popular will into tyranny, but did not imply a rejection of democracy itself.

Two decades later, Abraham Lincoln became the second president to use the term “constitutional republic” while in office. In the days after rebel forces fired on Fort Sumter but before the first major battle of Bull Run, Lincoln sent an 1861 message to the Congress noting that these events had raised the fundamental question of whether the American form of government could survive. “It presents to the whole family of man the question of whether a constitutional republic, or democracy — a government by the people by the same people — can or cannot maintain its territorial integrity against its own domestic foes.” It is telling that Lincoln clarified the unusual term “constitutional republic” with what he thought was an equivalent and more understandable one: “democracy,” and never thought these two were at odds.

Outright hostility to democracy was infused into the term “constitutional republic” by one of America’s most overlooked philosophers: Orestes Brownson. William Henry Harrison’s 1840 defeat of Martin Van Buren so crushed Brownson’s belief in the intelligence of the working class and his faith in popular action as a driver of historic progress that he abandoned his homegrown socialism and embraced Catholicism and conservatism.

In a series of three articles, published in 1843 in the influential United States Magazine and Democratic Review, Brownson detailed an astonishing rejection of core elements of the American government. Brownson attacked the Declaration of Independence as unnecessarily larded with false ideals like natural equality and unalienable rights. He tore into Jefferson’s principle that “governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed,” which he argued only led to the destruction of government itself. The root of the confusion bedeviling these much-ballyhooed founding ideals, Brownson theorizes, is a misconception of just who is “the people.” He deconstructs the idea of the public. “Does it mean the body politic, the people as a community; or the people regarded merely as individuals outside of civil society?” What Brownson meant by cleaving the people into two groups was that only those “legally convened” or constituted by the constitution and laws of the country were sovereign. The rest, the “mere mass of isolated individuals,” did not count and had no legal or moral standing. It is upon this distinction that the preservation of the nation depended. Its reckless overextension leads to “mobocracy … disorder, anarchy, license,” a “loose radicalism” that “holds that whatever for the moment is popular must needs be legitimate.”

Brownson’s critics blasted his retreat from democracy as being the natural consequence of his newfound Catholicism. “According to Mr. Brownson,” opined a typical editor, “it appears the existence of republicanism in this country would depend entirely on the will of the Pope, provided his adherents were capable of carrying out his orders.” But Brownson’s reworking of the idea of “the people” rested less on his Catholicism than on his newfound and profound distrust of majority opinion, if not people themselves. He clearly believed most were “lax in their morals,” lacking “manliness of character” as well as any “independence of thought and action.” He seemed to live in terror of multitudes of “demagogues, professing a world of love for the dear people … the better to fatten on popular ignorance and credulity.” In the end Brownson sighed, “I confess that I grow heartily sick of this doctrine, that ‘the majority has the right to govern.’”

In his third and concluding essay, Brownson asks What is the difference between a Democracy and a Constitutional Republic? He stripped the meaning of republic down to its bare timbers, including any arrangement in which “power is held to be a trust from the commonwealth to be exercised for the public good” rather than for “the private interest of the ruler or rulers.” Brownson justified his embrace of elite supervision over the messy churning of democracy by charging the term “constitutional republic” with the authority of originalism.

Now, according to these definitions, which is our government, a Constitutional Republic, or a Democracy? I do not hesitate a moment to answer for myself, that it is not a Democracy, but a Constitutional Republic, and that every effort to interpret it according to the democratic theory, is an attempt at revolution, and ought by no means to be encouraged by any who love their country, and desire individual freedom, or public prosperity.

These articles laid the foundation for Brownson’s 1865 political masterwork, The American Republic, a tome that would later be rediscovered and celebrated by philosopher Russell Kirk in his influential 1953 book, The Conservative Mind. Throughout his career Kirk would claim Brownson as one of the founders of modern conservatism. In addition to his anti-democratic theories, Brownson supplied the U.S. conservative movement with a shorthand for invoking them.

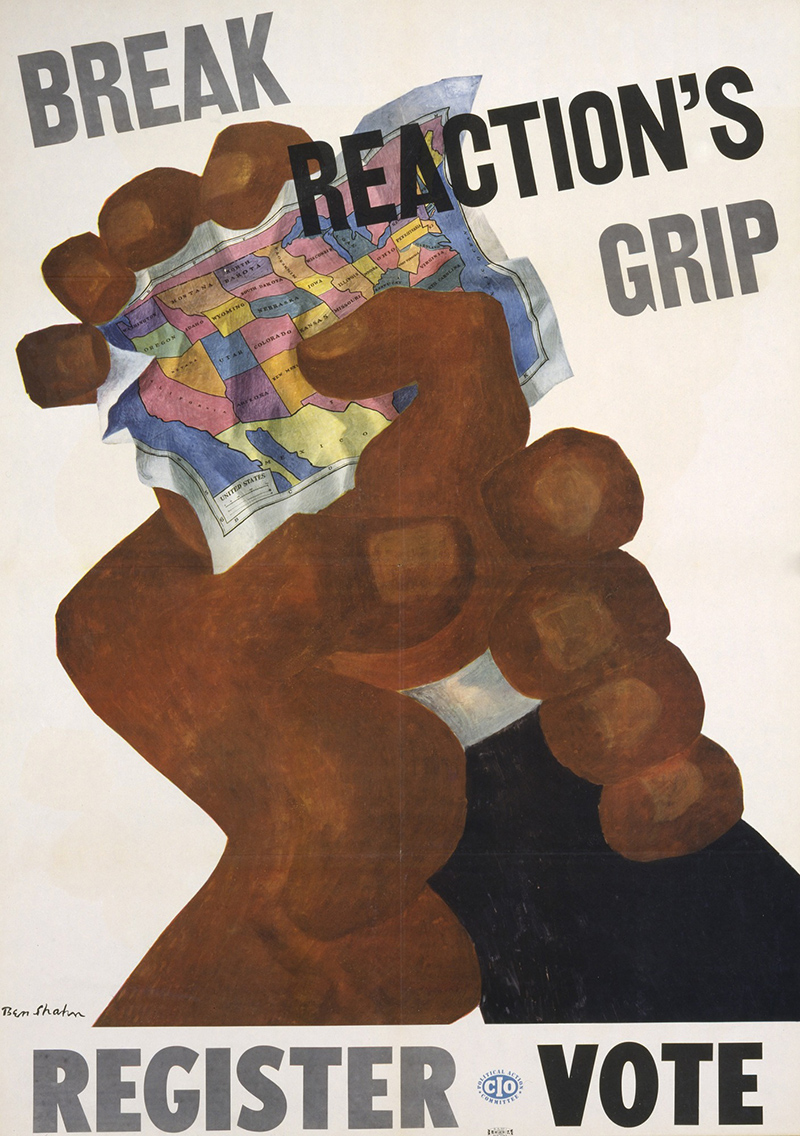

As the civil rights movement gained momentum after World War II, the American Right repurposed the phrase “constitutional republic” as a slogan to keep the movement in check. This strategy was expressed clearly in a 1950 unsigned editorial in The Southern Conservative, a racist journal whose masthead motto was a not-inaccurate characterization of white Americans at the time: “Millions of Americans think it — The Southern Conservative says it.”

We have Franklin D. Roosevelt to thank for making the transfer of authority from the States to the Federal government almost complete. He did this at the same time he was attempting to change the name of the United States from that of a Constitutional Republic to that of a “Democracy” ... That he got away with it until the day he died is tragic testimony to the weakened moral fibre and degeneracy of the American electorate which sank to the lowest depths of servility and groveling acquiescence under the New Deal and which seems unable to lift itself to a higher level.

In 1965, University of Chicago professor Richard Weaver, whose 1948 book Ideas Have Consequences was acclaimed for providing philosophical support to the modern conservative movement, articulated a view of the Constitution not as the structure of democracy but rather as its counterbalance:

Democracy finds it difficult ever to say that man is wrong if he does things in large majorities. Yet even politically this notion has to be rejected; and that is why constitutions and organic laws are created in nearly all representative governments … A constitution is a government’s better self, able to rebuke and restrain the baser self when it starts off on a vagary. If the mass of every electorate were wholly right at every period, constitutions would be only curious encumbrances.

From this it is only a short hop to venerating America’s “constitutional republic” and expunging references to its democratic institutions.

Conservatives eventually took aim at the nation’s schools as a vital frontline against communism and racial equality. The term “constitutional republic” proved useful, simultaneously exalting private property, local control of schools, “states rights,” and personal liberty, all of these being projects to exempt vast areas of society from collective decision-making.

One of the founders of the National Review, Edward Merrill Root, first splashed into prominence with the publication of his 1958 book Brainwashing in the High Schools. Root scoured through many of the history textbooks commonly assigned at that time and concluded that “None of these eleven textbooks in American history makes it clear that the government of the United States of America is not a democracy — but a republic. Not a single text defines even democracy in its true American sense, enabling students to see how essentially it differs from the contemporary ‘people's democracies’ that disfigure the world. Our American form of government is not a "democracy" at all. The Founding Fathers defined the form of government which they set up as a constitutional republic.”

Root eventually became an editor of the John Birch Society’s magazine, American Opinion. It may have been the Birchers who most dramatically employed the term “constitutional republic” as a means of justifying anti-democratic authoritarianism. The John Birch Society’s Blue Book, first published in 1959, republished a speech by its founder Robert Welch attacking democracy as a Trojan Horse of socialism. “A republican form of government … lends itself too readily to infiltration, distortion, and disruption. And democracy, of course, in government or organization, as the Greeks and Romans both found out, and as I believe every man in this room clearly recognizes — democracy is merely a deceptive phrase, a weapon of demagoguery, and a perennial fraud.” The appended footnote to Welch’s comment is even more revealing:

Our liberal critics would have you believe that this statement, for an American, is practically heresy. This is because these same liberals have been working so long and so hard to convert our republic into a democracy, and to make the American people believe that it is supposed to be a democracy. Nothing could be further from the truth than that insidiously planted premise. Our founding fathers… visibly spurned a democracy as probably the worst of all forms of government. But our past history and our present danger indicate that they were right in both particulars.

Welch repeated these sentiments frequently; one speech he gave on Constitution Day in 1961 was reprinted in newspapers across the country and in the conservative press ever since.

I think that a constitutional republic is the best of all forms of government man has yet devised. Our Founding Fathers thought so too … To that end we are saying everywhere we can, and asking all of you and tens of thousands to say with us: This is a Republic, not a Democracy. Let’s keep it that way!”

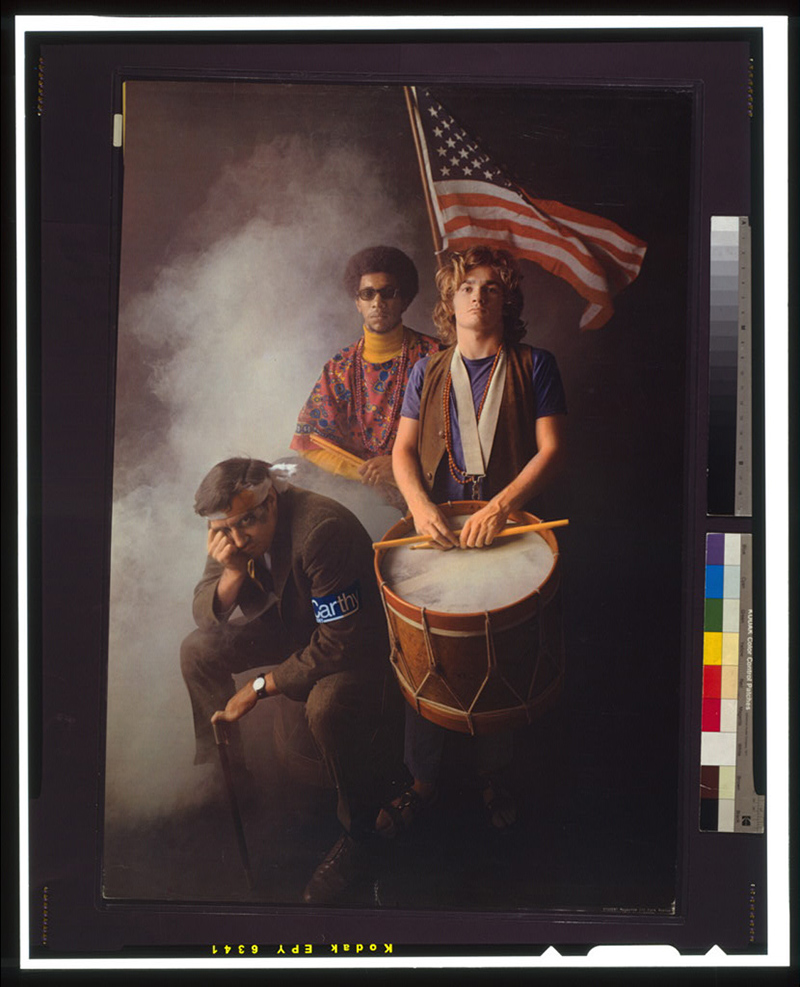

The phrase “constitutional republic” was picked up by the GOP mainstream and used in the 1964 presidential platform of Barry Goldwater, which bemoaned that “in this Constitutional Republic … individual freedom retreats under the mounting assault of expanding centralized power.” The term then retreated into the recesses of far-right organizations until the election of Barack Obama, when it was flung about during the 2010 Tea Party Convention and was deployed by various conservative senators in opposition to Obama’s healthcare reforms.

Around the same time, various right-wing organizations like the Federalist Society began publishing white papers advocating for the repeal of the Seventeenth Amendment, which allows for the direct election of senators. In its 2017 “Handbook for Policymakers,” the conservative Cato Institute urged that it was time to once again “invoke the doctrine of enumerated powers” as a way of fighting the various “rights” activist courts had “discovered” in the modern era. “If the Framers had wanted to establish a simple democracy, they could have. Instead, they established a limited constitutional republic.”

Sometimes the idea was simplified into slogan, as when Utah Senator Mike Lee wrote just before the 2020 election, “Our system is best described as a constitutional republic … democracy itself is not the goal.” Pete Hegseth tweeted on July 4, 2024, “Here’s a quick reminder of what our founders gave us: a Constitutional Republic, NOT a Democracy. If we can keep it…”

The latest campaign to root out references to democracy in public schools took off in Texas when it revamped its state social studies curriculum in 2010 and dropped references to America being “democratic,” replacing them with the term “constitutional republic.” In 2017, West Virginia state lawmakers established “Celebrate Freedom Week,” during which all public school students were to study the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution to understand how the “founding fathers” succeeded in “safeguarding our constitutional republic.”

In 2018, GOP legislators in Michigan attempted to delete nearly a dozen references to “democratic values” and add the phrase “constitutional republic” 36 times in that state’s social studies standards. The following year, Nebraska’s legislature edited out from its state educational standards that the goals of its schools was to ensure that “the love of liberty, justice, democracy, and America will be instilled in the hearts and minds of the youth of the state.” Not quite prepared to throw out the idea of democracy, Nebraska split the difference by rewording a part of this section to read: “The youth in our state should be committed to the ideals and values of our country's democracy and the constitutional republic established by the people.”

Such changes have long been pushed by right-wing think-tanks. Citizens for Objective Public Education explains the effort bluntly: “We prefer the term ‘constitutional republic’ … [existing] standards choose to refer to the United States as a constitutional democracy, while we think a more accurate description is a constitutional republic.” The Civics Alliance, a project of the conservative National Association of Scholars, drafted model legislation called the Civic Intent Act, identifying it as “legislation to teach the ideals of our constitutional republic.” Its model social studies curriculum requires that state guidelines “shall include the rights and responsibilities of citizens of our constitutional republic” and never uses the word “democracy.”

The word “democracy” does not appear in the introduction to Hillsdale College’s 1776 Curriculum. In these guidelines, elementary school teachers are to

Clarify that the Constitution establishes a republic, not a democracy. In a pure democracy the people make all legislative decisions by direct majority vote; in a republic, the people elect certain individuals to represent their interests in deliberating and voting.

Third to fifth graders are asked directly to explain what a “constitutional republic” is. By high school civics teachers are told to instruct students “about the conditions necessary for the flourishing and perpetuation of freedom and self-government, particularly in a constitutional republic.” In 2023, South Dakota adopted the Hillsdale standards. The movement has attempted but failed to implement similar changes in half a dozen other states.

In 2024, Utah required that instructors specify that the “United States’ form of government [is] a compound constitutional republic.” This detail was lost in the controversy that erupted in this bill’s requirement that the “Ten Commandments” be taught as one of the “American heritage documents.” In 2025, new social studies standards in Oklahoma injected the phrase “constitutional republic” into its latest curriculum standards. The change was overshadowed by the new curriculum’s requirement that instructors teach about “discrepancies” in the 2020 presidential election.

This quiet campaign to rewrite the principles of American government even had success in a blue-state assembly controlled by Democrats. In 2021, as debate over new social studies guidelines stretched into the night, the vice chair of the Colorado Republican party snuck in what seemed like minor changes that were approved on a routine vote. He deleted the phrase “democratic government” and replaced it with “the Constitutional Republic form of government”; eliminated all three references to “democracy” replacing them with “republic”; and changed a reference to "democratic processes" to “the constitutional republican process.”

This stealth movement has up until now primarily focused on K-12 standards, but higher education could be next. In May 2023, Florida became the first state to specify that its public colleges and universities had to “promote and preserve the constitutional republic through traditional, historically accurate, and high-quality coursework.” The state’s students may one day discover that the sense in which its leaders interpret their “constitutional republic” is neither traditional nor historically accurate.