A Ghost from Kitchens Across the Nation

World’s Fair, 1893. Photograph by C.C. Hyland. [Library of Congress]

While most Americans today would likely be hard put to name a modern-day conjure woman if asked, a caricature of one smiled warily at them from their kitchen cupboards for over a century: Aunt Jemima, Pearl Milling Company’s cherished pancake mix mascot. Introduced in 1889, Aunt Jemima is a fictious character based on Negro Mammies, enslaved women who held a central place on plantations. They were women like Harriet Collins and Harriet Jacobs, women who played a major role in the development of American food traditions and medicine. Negro Mammies were conjure women who used local flora to heal minor ailments; nursed all the children on the grounds, both Black and white; cooked and organized food in the Big House; provided advice to younger enslaved women; and offered spiritual comfort, often by way of mojos, sacred amulets, to the enslaved.

Mojos were a staple of hoodoo, a conjure tradition that developed in the Deep South and lower East Coast. Mojos often gave the oppressed confidence to rebel against their oppressors — slave against master, wife against husband. This use of mojos would live on well into the twentieth century, becoming one of the defining aspects of African American culture, especially our music.

While newly freed African Americans were busy telling stories about the mojos of Negro Mammies in their early blues songs, the American public began to wax nostalgic over plantation life. In the eyes of the American public, the Negro Mammy was a docile slave who championed the institution of slavery. The national worship of Negro Mammies reached a fever pitch in 1923. At the start of that year, a bill was put forward in the Senate to erect a million-dollar marble and granite statue of their beloved Negro Mammy in Washington, DC.

Most white Americans never even had slaves, much less been raised by a Negro Mammy. So how did the Negro Mammy, a figure who was tucked away on rural southern plantations, a figure who was relatively obscure in the nation before the Civil War, become a wildly popular national icon and lightning rod of racial conflict?

It began with a party.

In 1893, the United States government decided to throw a grand party in Chicago: the World’s Columbian Exposition, an international fair to celebrate the four hundredth anniversary of the “discovery” of America by Christopher Columbus in 1492. (The complications in setting up the fair, a daunting task in the then largely industrial and hardly picturesque Chicago, made the fair a year late for the anniversary.) At the World’s Fair, several countries, from neighboring countries like Mexico to countries in the Far East, like Japan, were invited to set up an exhibit. The World’s Fair organizers wanted to display to the nations — especially Europe — how far the United States of America had come in four hundred years; they wanted to stress that our wild democratic experiment had been a success. The evidence of that success was our rapid technological innovation at the turn of the twentieth century.

And if you were one of the twenty-seven million people who purchased a ticket to the fair for fifty cents between May and October, you would have indeed been privy to grand feats of innovation that showcased American ingenuity: the world’s first Ferris wheel, a 264-foot-tall wheel that spun on a seventy-one ton axle, carried thirty-six cars that could fit sixty people at a time, and whose heights rivaled the Eiffel Tower, which was featured in the 1889 World’s Fair in Paris; electric lights whose colors danced to music and whirled in fountains at a time when most Americans were still using oil lamps to light their homes; one of the first electric train lines, ferrying visitors on a loop in the air over the fair’s 663 acres; and Thomas Edison’s kinetoscope, which displayed a mesmerizing precursor to movies.

The contributions of African Americans were noticeably missing from this grand celebration. The World’s Fair organizers refused to include African Americans in the fair’s planning, actively barring our proposals for booths that showcased our extraordinary cultural and economic progress achieved merely thirty years after enslavement. The proposed booths would have been astounding to an American public who believed we would never rise above the status of lowly, ignorant servants. By the 1890s, we had doubled our literacy rate, providing a robust education to thousands of Black people who, under slavery, had been violently prohibited from learning to read or write. We had tripled the number of books written by African Americans. And there was a significant increase of African Americans who took up the professions of teaching, ministry, medicine, and law.

In the end, it was Haiti, not America, that gave African Americans a place at the Chicago World’s Fair. Haiti, like many other countries, was represented at the World’s Fair with its own dedicated building. The Haitians opened their doors to African Americans to voice their complaints about and their contributions to the nation. Ida B. Wells, at the time an investigative journalist, partnered with other leading Black intellectuals — Irvine Garland Penn, Ferdinand Lee Barnett, and Frederick Douglass — to produce a pamphlet called “The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition.” Wells stood on the steps of the building dedicated to Haiti at the World’s Fair, passing out copies of this pamphlet to the visitors from all over the globe who stopped to gaze upon and consider the first and only free Black republic in the New World.

In the pamphlet, Wells pointed out that the wealth created by African Americans’ industry has afforded to the white people of this country the leisure essential to their great progress in education, art, science, industry and invention. Wells understood that to try to tell the story of America without African Americans is as foolish as building a house upon shifting sands — which was exactly the physical construction of the fair.

At the center of the fair was a gleaming “White City” that swayed on stilts. Workers had cleared forlorn-looking oak and gum trees in the large muddy swamp of Jackson Park, which sat on the shore of Lake Michigan. They drove large stilts deep into the sandy marsh to support six large buildings of stucco — a low-cost plaster. They painted these cheap buildings bright white to look as if they were marble. Styled after Greek and Roman architecture, these six buildings formed a square called the Court of Honor, showcasing the major areas of innovation in America: liberal arts, agriculture, anthropology, electricity, machinery, and mining. These hastily built, faux marbled buildings on shoddy foundations were to be the symbols of American progress. And so, the Court of Honor, a make-believe city, held all the tensions of the American dream: buildings with a gleam so white, so bright, they detracted from the muck below that upheld them.

It was in the Court of Honor’s agriculture building that you would find the exhibit of Aunt Jemima’s pancakes. Many of the products that were sampled in this building are still found in our grocery stores today, over a hundred years later, such as Quaker Oats, Cracker Jacks, and Wrigley’s Chewing Gum.

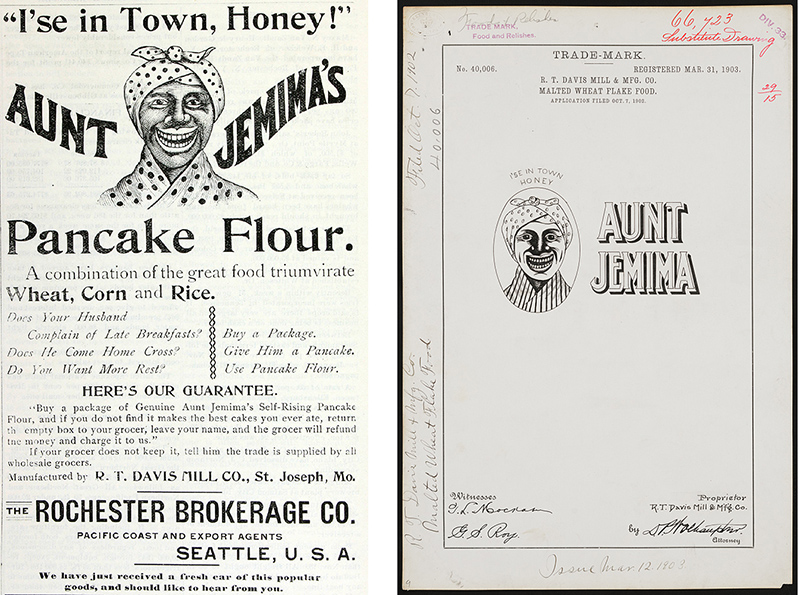

In 1890, R.T. Davis, the president of Davis Milling Company, bought Aunt Jemima’s pancake mix from Chris Rutt and Charles Underwood, who first developed the product in 1889. The first self-rising flour mix on the market, Aunt Jemima’s pancake mix was made of wheat, rice, and corn. This was a striking departure from the pancakes of the South — called hoecakes, ashcakes, johnny-cakes, or pone — which were typically made from cornmeal. To market this unfamiliar product to the American public, Chris Rutt decided to draw upon the preeminent form of entertainment in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century: minstrel shows, where white men darkened their skin with burnt cork to imitate the songs and dances of the enslaved.

Fairgoers who visited Aunt Jemima’s pancake exhibit would have recognized her name from “Old Aunt Jemima,” a staple song and skit of the minstrel circuit. When Rutt heard the song performed in an 1889 minstrel show and saw how popular it was among the crowd, it struck him that Aunt Jemima would be the perfect “face” for his product. After the show, Rutt plastered a grotesque painting of Aunt Jemima on every newspaper, magazine, and paper box advertising their new pancake mix. R. T. Davis took the branding further by casting Nancy Green, a formerly enslaved Black woman, to play the role of Aunt Jemima at the World’s Fair.

At the pancake exhibit, an enormous barrel of pancake flour loomed behind Green. At 16 feet high, 12 feet wide, and 24 feet long, this barrel was bigger than the average SUV. Draped in an apron and donning the Negro Mammy’s customary red bandanna, Green flipped over one million pancakes over the six months the fair was in operation. While she made pancakes, she sang spirituals and relayed stories about the “good old days” of slavery. It was said that the exhibit drew a crowd so large the police had to step in to keep the walkways clear. The live advertisement was an incredible success, fetching over 50,000 orders of Aunt Jemima’s pancake mix from fair visitors hailing from all over the country. Due to her laudatory reception, the officials at the fair named Aunt Jemima “Queen of the Pancakes.”

Consider the souvenir gift of the exhibit: a button pin featuring a smiling Aunt Jemima with the phrase “I’se in town, honey!” scrawled across the top. Aunt Jemima’s successful move from the rural, southern plantation to the bustling, urban “town” of the North (like Chicago) is predicated upon her willingness to remain a servant, a Negro Mammy to whites. This sentiment captures the attitudes of both northern whites who were agitated by the influx of African Americans and southern whites who were dismayed at the loss of their workforce during the mass migration. Through Aunt Jemima’s pancake mix, the longed-for Negro Mammy could return to white kitchens once again.

But while white Americans saw in Aunt Jemima the docility and domesticity of the Old South, African Americans took something entirely different from the exhibit. African Americans, too, were familiar with the song “Old Aunt Jemima” — but it held a radically different meaning. African American minstrel performer and former slave Billy Kersands originally came up with the “Old Aunt Jemima” song and dance routine in 1875. And when African Americans came onto the minstrel stage, they often added layers of nuance to the routine that whites did not pick up on. After all, it was an incredibly ironic performance: African Americans were mocking white Americans, who had built a career out of mocking their castmates’ days of enslavement.

As scholar M.M. Manring observes, Kersands’s “Old Aunt Jemima,” which impersonates a Negro Mammy, is based upon a slave song called “Promises of Freedom.” This song added a great irony to his act, subtly making fun of the very whites who enjoyed minstrel shows. In the song, the enslaved ridicule slave masters who made vacuous pledges of future manumission. One verse features a mistress who promised to free the enslaved upon her death. Rather than fulfill her promise, she simply refuses to die, going plumb bald in her old age.

Whites in America did not realize that by welcoming Aunt Jemima into their homes, they were not only gaining access to her delicious pancakes; they were also partaking of the conjure African American women have been wielding for centuries. Beneath the light melody and playful dance that accompanied the song “Old Aunt Jemima,” the lyrics issued a deadly serious threat: a mojo used by the enslaved to get back at their masters who failed to uphold past promises of freedom.

When Rutt’s Aunt Jemima and Kersands’s “Old Aunt Jemima” are laid side by side, they tell a story of two different Americas. At the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, Aunt Jemima’s pancakes gave whites the America they longed for — one where newly freed African Americans embraced the docility and domesticity posed by an imaginary Negro Mammy. But “Old Aunt Jemima” describes an America that has fallen short of providing the freedom it guarantees to all its citizens — an America that newly freed Blacks wanted to hold accountable for such failings. In Black America, Aunt Jemima rises like a ghost from kitchens across the nation, wielding the mojos of past Negro Mammies. Behind this popular pancake mix stands a secret history where Aunt Jemima is no longer a slave but a Black revolutionary.

Excerpted from the book The Conjuring of America: Mojos, Mermaids, Medicine, and 400 Years of Black Women’s Magic by Lindsey Stewart. Copyright © 2025 by Lindsey Stewart. Reprinted with permission of Legacy Lit, an imprint of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.